Data matters in meteorology. Some of the most underrated data in the country, in my opinion comes from personal weather stations, groups of weather stations called mesonets, and airport weather stations. While satellite, radar, and model data can highlight and suggest threat areas, weather stations can directly observe, quantify, verify, and sample conditions. Surface observation data that is shared with NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and the NWS (National Weather Service) is also used in computer forecast models and for verification of weather conditions – including rainfall totals and wind gusts in active or severe weather situations.

It can take years to get existing and new points of information on the map integrated into one place, but it can be done. Official weather records are great, but there is often an incredible amount of space between these sites, and daily, comprehensive weather records (including those with wind, snow depth, and snowfall totals) are almost entirely limited to airports in larger cities.

This blog post focuses on three things: 1) how the data flows, 2) how do get data into the data streams, and 3) how to fix errors in data points flowing into the data streams.

All of this information is publicly and freely available on the Internet. There is nothing propriety here, and I link to public sites throughout the article. The data streams themselves are public, and that’s the way they should be. The more weather data that is public, the more that is accessible to those who need it. My hope is that more data will be added to the streams over time so that the weather can be better understood and verified.

How The Data Flows

The ultimate goal is to get weather data to NOAA and NWS.

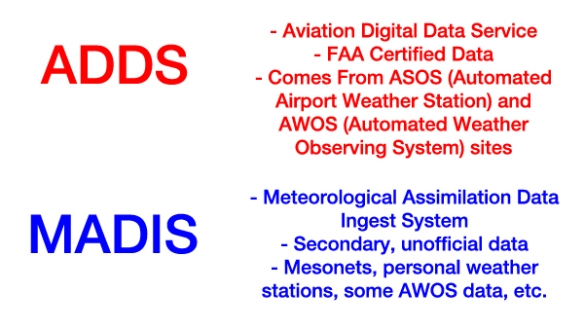

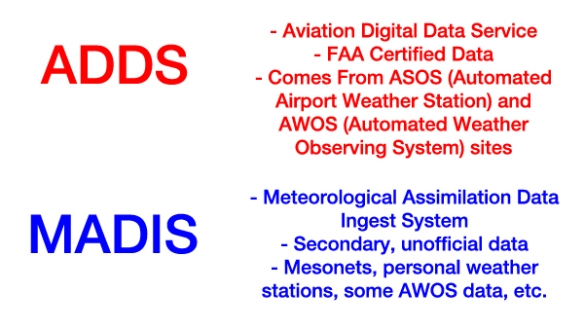

Before we start pushing data into the streams, we must first understand how the streams work. There’s are two main NOAA data streams: the ADDS and MADIS. It is important to know the difference:

ASOSes are controlled cooperatively in the U.S. by the NWS, FAA, and DOD, and the data from them flow to ADDS. AWOSes can be controlled by the FAA, local or state governments, or private groups. Data from an AWOS can go to ADDS or MADIS, and not all AWOS data goes to MADIS or ADDS. ASOSes are superior in some, but not all, ways to AWOSes. You can verify which ASOSes and AWOSes share their data with ADDS by putting in an airport code or ICAO here:

http://www.aviationweather.gov/metar

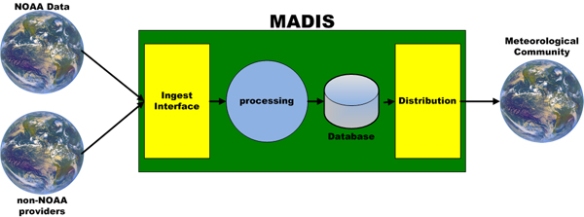

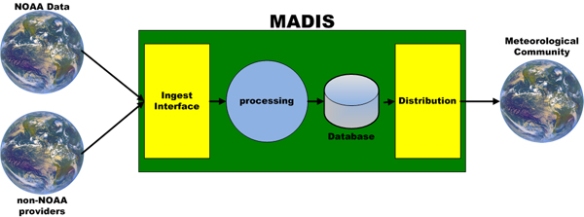

MADIS’ website shows the flow of data through MADIS looks like this:

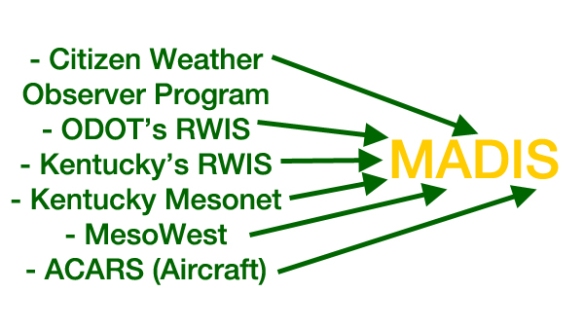

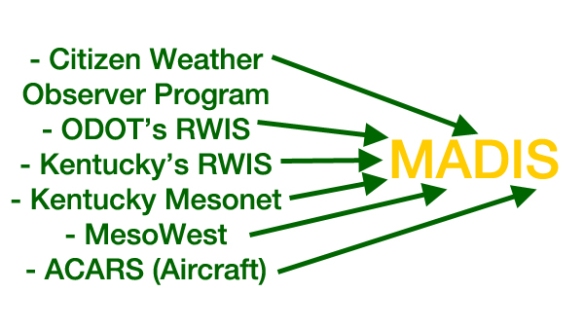

This process is very similar to that of ADDS data except FAA certified data is the only input to ADDS. MADIS takes just about everything else that’s left (that doesn’t flow to ADDS). Here are some example inputs to MADIS:

While not “official,” MADIS is very important. As of the writing of this blog, there are 34,191 points of surface weather data flowing through MADIS from 74 different networks or mesonets. About 25.4% of those observations come from the Citizen Weather Observer Program (CWOP), where personal weather stations share their data to NOAA (more on this below).

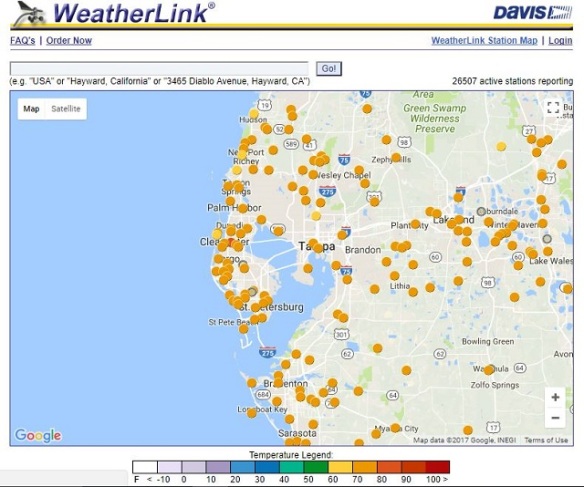

NOAA’s MADIS map shows all of the publicly available MADIS sites and ADDS sites. MADIS sites are the ones that do not appear on the ADDS map. You can verify this by looking at the MADIS and ADDS maps. Not all data collected by MADIS is redistributed to the public; you can review what MADIS data goes where here.

Much of the discussion below focuses on CWOP, Roadway Weather Information Systems (RWIS), Weather Underground, AWOS, and WeatherLink IP data. These are all low-hanging fruits compared to growing the other weather networks.

How To Get Data Into The Streams – CWOP

First, let’s focus our efforts on CWOP and how it works. Some, but not all, personal weather stations – through either hardware, software, or both – will share data to CWOP.

The basic steps to get personal weather station to CWOP are:

1) Get a CWOP ID unless you’re an amateur radio operator

2) Configure the weather station software to share data with CWOP

3) Verify CWOP is getting the data

3) Register the station with NOAA by e-mail

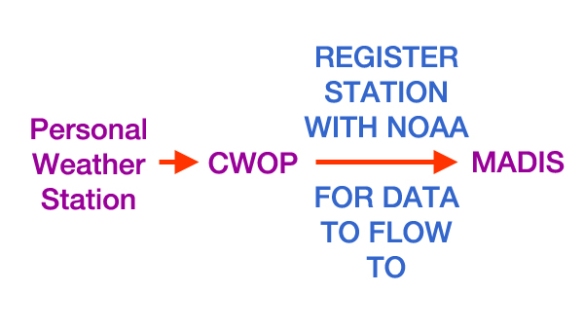

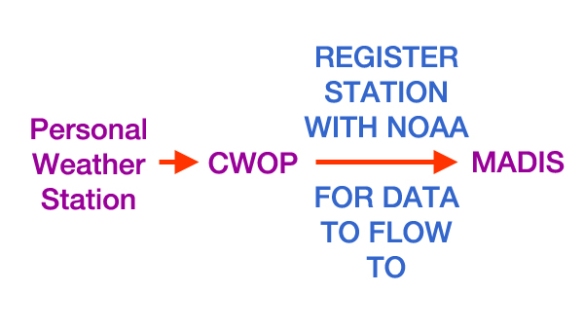

Visually, this is the goal:

It’s important to note that just because data goes to CWOP doesn’t mean it goes to MADIS! The weather station owner must register their station with NOAA for the data to flow to MADIS. Please see the note on checking to see if their are unregistered sites for a given state in the “How To Fix Errors In Data Points Flowing Into The Data Streams” section below.

Like I said above, not all weather stations can share data with CWOP. These can’t:

– AcuRite Pro Weather Center

– Neatmo

– Ambient Weather WS-1000

– Ambient Weather WS-1001

To repeat, if an owner of one of these weather stations wants to share data with CWOP, it can’t be done and you should give up trying immediately!

With this considered, let’s move to step two. How do you share data to CWOP? It’s easy if a weather station owner has a Davis WeatherLink, WeatherLink IP, or popular weather station software (MeteoHub, MeteoBridge, Virtual Weather Station, Cumulus, WeatherSnoop, or WxDisplay) because all of the directions, produced by the National Weather Service in El Paso are here:

https://www.weather.gov/epz/cwopEPZ

There are the step-by-step directions for sharing the data with the world. Add it to your bookmarks if you need to! Click here for more information on sharing data from weather station software.

Once we’ve configured the software, we need to verify that CWOP is getting the data. CWOP should have an inventory of the data in no more than 30 minutes, but it may be there in as little as 5 minutes. Weather reports on CWOP’s page will surface here: http://www.findu.com/cgi-bin/wx.cgi?call=XXXXX, where XXXXX is the CWOP ID or amateur radio handle. Also, once the data starts showing up on this page, please check to make sure the weather station latitude and longitude are correct here: http://www.findu.com/cgi-bin/find.cgi?call=XXXXX, where XXXXX is the CWOP ID or amateur radio handle. A minus sign may be needed on the longitude to get you into the western hemisphere.

If the weather data makes meteorological sense and the location on the map is correct, we are in good shape. If these items are wrong. check the settings in the weather station software. See my note on the minus sign for the longitude above.

Important: we are not done yet! We still need to register the weather station with NOAA. When the settings are right, have the weather station owner send an e-mail to CWOP support (cwop-support@noaa.gov) requesting to register the weather station with CWOP; in the e-mail, include the CWOP ID, the closest town to the weather station (use a specific community), zip code, and the weather station’s elevation in meters (not feet). If the weather station owner gets an e-mail from NOAA CWOP support, verify the date that they will add you to the MADIS map…along with the CWOP ID. This is an important step because registering the station ensures the data will flow to the world through MADIS.

It’s important to note that the siting of the weather station matters! More on proper siting for this can be found here. You can share this PDF with weather station owners to help them correct weather station data biases.

How To Get Data Into The Streams – RWIS

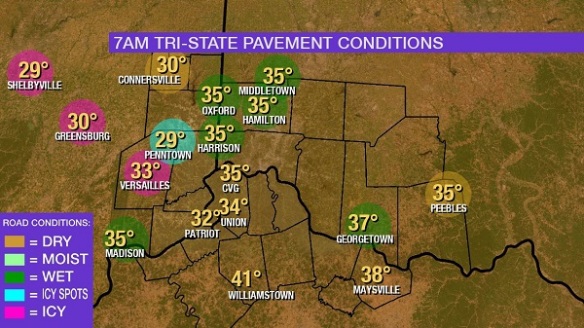

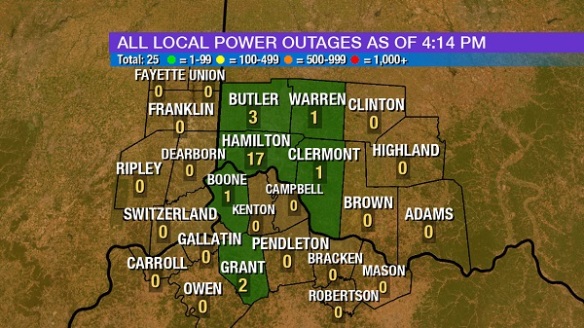

Roadway Information Systems (RWIS) are weather networks owned and operated by state departments of transportation (especially in colder climates). Some networks are robust, and others are weaker. The data that comes from these networks are still very important!

Odds are good that the state is already sharing the data from all of their RWIS sites, but you should check because you might be surprised! MADIS don’t always configure their redistribution systems to share all RWIS data as new RWIS sites come online.

The goal here is to:

1) Find the state’s official RWIS website

2) Compare the sites on it to NOAA’s MADIS map and make sure none of the RWIS sites are missing

If all of the RWIS sites are there, you’re good to go. If not, e-mail madis-support@noaa.gov and bring it to their attention. They are there to help you and can work with a state’s RWIS contact about sharing data and troubleshoot errors.

If there are problems with the data coming from a specific RWIS site, that falls under the responsibility of the state department of transportation. Contact them directly to fix individual RWIS site issues.

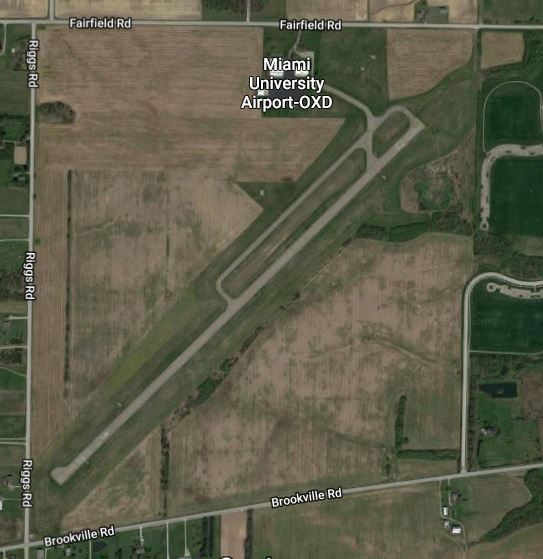

How To Get Data Into The Streams – AWOS

Most AWOSes are located at airports, and some AWOSes don’t share their data with MADIS or ADDS. The first step here is to find the airports that have an AWOS that aren’t sharing their data with MADIS or ADDS. You do that by:

1) Using the FAA’s ASOS map to see where there are ASOSes and AWOSes

2) See if those same sites are on NOAA’s MADIS Map

Once we’ve found a site that is on the FAA’s ASOS map and not on the MADIS map, we need to get the airport identifier (ICAO) for the site. Next, we need to get in touch with the airport manager. Legally, the airport manager’s name, address, and contact number must be listed in FAA records. You can get this contact information by putting the airport ID or ICAO into this website:

http://www.airnav.com/airport/

It is now your goal to convince the airport manager to share their AWOS data – through a vendor – to either ADDS or MADIS. Googling “AWOS vendors” will give you a list of the vendors. Sharing data with MADIS is cheaper, and sharing data with ADDS is more expensive (because it’s FAA certified). If you’re a member of the media, saying you’ll share their airport AWOS data with the community on-air helps persuade them to pay a vendor to share their data. If you’re a pilot, saying you’ll use the data for safety will help. If you’re member of the community, you can say you just want to put the community on the map.

Precipitation type and intensity sensors are not required on FAA certified AWOSes (all ASOSes and nearly all AWOSes themselves are FAA certified, but the feed out of them does not have to be). Having this precipitation information in a weather report is helpful, but the sensors cost money. This can be a hard sell to an airport manager, but it can be done. Keep in touch with them, and be persistent, and you’ll eventually get the sensor.

How To Fix Errors In Data Points Flowing Into The Data Streams

CWOP

– As I alluded to earlier, there are registered CWOP stations and unregistered CWOP stations. The data from the latter does not flow to MADIS. Think of the latter as a TV that doesn’t have the cable connected correctly into the back of it; you just want to complete the transmission.

– The easiest way to view registered and unregistered CWOP site is on the CWOP website and by state. You can find the page for a given state by clicking on the map under the “Data Time History Displays” here. Clicking on Texas, for example, will bring you to list of registered stations here. Notice the e-mail contact information for each weather station owner is listed on this page. Clicking on “WxGraph” for each site will allow you to see recent trends in weather data or show you that CWOP hasn’t received data from that site in a while; if there’s no recent data for a site, you can reach out to that weather station owner via e-mail to notify them they haven’t been sharing data in a while, ask them to check their weather station, or ask them to look at a sensor if their data is inaccurate. If you scroll down the page, you’ll see a link that says “UNREGISTERED XXX MEMBERS WITH UNVERIFIED STATIONS,” where XXX is the name of the state. An example for the unregistered Texas page is here. This is a list of people that registered for a CWOP IP but they didn’t register their station with NOAA. Just because they didn’t register their station with NOAA doesn’t mean they aren’t sharing their data with CWOP! Clicking on the “WxGraph” link for a site will show you recent data CWOP has received from that weather station owner. You might find a site that has site that you want to flow to MADIS; if you encounter this, e-mail the weather station owner and ask them to register their station with NOAA (see e-mail to cwop-support@noaa.gov directions above). Even if a unregistered weather station owner isn’t sharing data to CWOP, you know they are at least interested in sharing data with CWOP and probably own a weather station; you might as well get that data! E-mailing them and seeing what their situation is will helpful. You might find they just hadn’t gotten around to getting their weather station setup and may be excited you’re using their data (especially if you’re in the media or another public setting). The CWOP site gives you their first name, which is a good start for relationship building and networking.

Weather Underground

– Weather Underground (WU) data does not flow to MADIS. They are actually kind of jerks about it when you do some research.

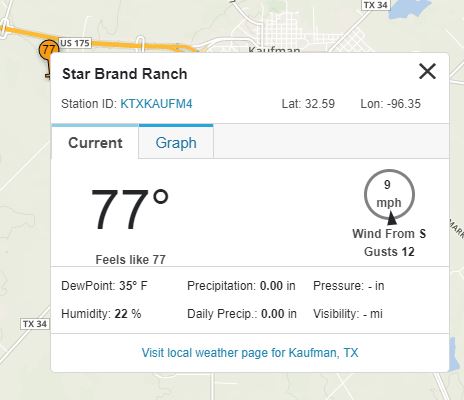

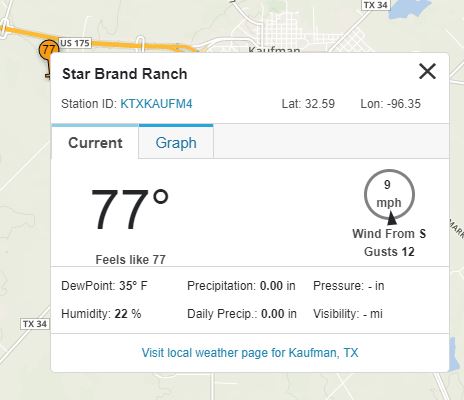

– There is, however, a workaround for most but not all weather stations: contact the weather station owner and ask if they will share their data to MADIS and WU (actually, I prefer they do because WU has good weather archives). First, find a site on Weather Underground that you would like to see on MADIS. I’d suggest using the Wundermap. Here’s an example from Kaufman, Texas:

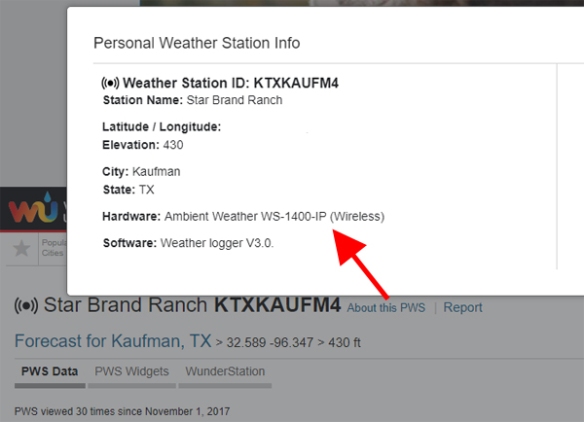

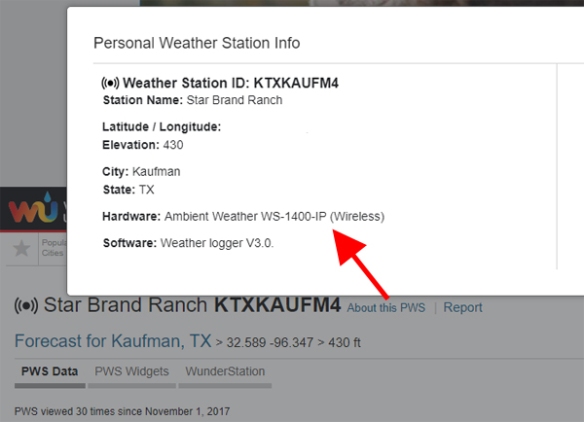

If I click on the Station ID link (the KTXKAUFM4 part), I’m taken to this website. If I click the “About this PWS” link here in the top of the page, I see this window pop-up:

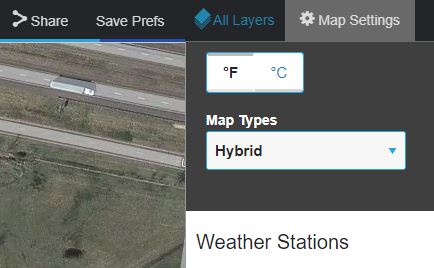

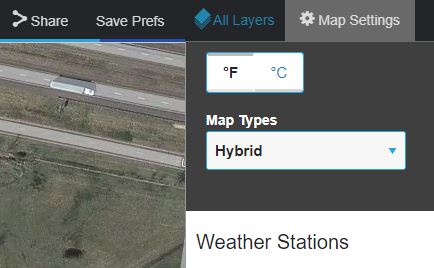

The first thing to notice here is that it not on my list of forbidden, dead end weather station brands and types above, so there is hope we can get this weather station into MADIS. So how do we contact them? We could message them if we have a WU account, but this is a dead end. We want to convert their latitude and longitude to an address and mail them a letter. Go back to the Wundermap and zoom in down to street level on the weather station; also, turn the “Map Types” in the upper-right corner to “Hybrid”:

Once these settings are set, we see the map looks like this:

There’s a really good chance here that that homeowner owns that weather station. If this was a densely populated neighborhood, we might have to get in closer and try to figure out if the weather station is in the backyard of one house or the front yard of another.

So how do we get their address? Take their latitude and longitude and put into Google Earth and see where they are and what county they are in. This station is in Kaufman County, Texas. The easiest way in the modern era to get an address is through GIS, or Geographic Information Systems. If you Google the name of the county, name of the state, and “GIS,” you’ll likely get a government website that can use to get you to an address. In the example, Google searching “Kaufman County Texas GIS” gets you to an interactive map where you can get an address.

– Have the courage to contact someone. I know it’s weird to send someone a letter in the mail out of the blue, but you can do it…and if you want their data, you’ll have to.

– Once the person e-mails you, you can greet him or her, and explain that you’re trying to direct their weather station data to MADIS, and send them step-by-step directions to configure their software using this page that I linked to above. You may have to Google directions for other weather station software types.

– Most weather station owners, with the right approach, will share their data with MADIS. Some will not; for those that don’t want to share, you might try asking again in a year or so.

AWOSes

– When there’s an error in data, call the airport manager. They don’t want bad data from their airport being broadcast to the world.

– It’s worth noting that the clocks inside AWOSes tend to drift. If the clock drifts into the future, NOAA will reject the observation (observations don’t come from the future), and you won’t get the data through ADDS or MADIS. You fix this issue by calling the airport manager, telling them this, and convincing them that their AWOS technician needs to check the AWOS clock once a month (they can adjust this remotely).

Davis WeatherLink IP Stations

Once you get the hang of how to get WU stations into MADIS, try your hand at getting Davis WeatherLink IP weather stations online. Davis’ WeatherLink IP website is here:

http://www.weatherlink.com/map.php

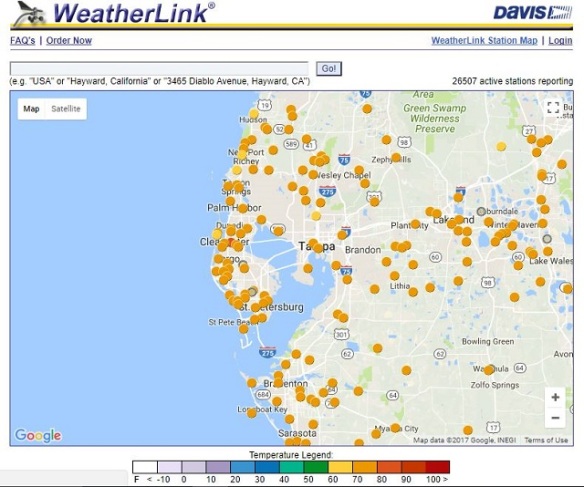

There are many weather stations on here that you won’t really be able to find anywhere else. Here’s a snapshot of Davis WeatherLink IP weather stations (dots) in the Tampa area:

Before we start contacting everyone on this map, remember that:

1) WeatherLink is not the same as WeatherLink IP. In a WeatherLink setup, data flows from the Davis weather station to a computer and then to CWOP. In a WeatherLink IP setup, data flows from the Davis weather station to CWOP through Davis’ servers; WeatherLink IP owners still must have a CWOP ID so they can push their data to CWOP!

2) Some WeatherLink IP owners are already sharing their data with CWOP and/or MADIS. You can verify whether the data are flowing to MADIS on NOAA’s MADIS map.

3) There will be obvious cases when the position of the weather station is wrong (in a field, over water, etc.). Clicking on each of the dots on the map may give you clues about a location (a business or organization name), an address (123 Easy Street), or someone’s name (J. Richardson). If you only get a name, use the location (latitude/longitude) on the Davis WeatherLink IP map and county GIS webpages to find the address in the latter and see if the name makes sense. You might find a John Richardson two houses down from where you thought on the GIS maps, and that is likely the person you want.

Human Processing Still Required

There will be times when weather stations go offline or report information that is clearly wrong. It is up to you to find ways to – over time – remedy the problems or find ways to quality control – either in your own mind or with a computer – the errors included in the data. Don’t get burned presenting a 0.00″ rainfall total from MADIS on a rainy night or a -40° temperature on a spring day!

Here To Help

Questions? Comments? Issues? Concerns? I’m here to help. You’re welcome to contact me at the “Contact Me” link near the top of the page.