While the courtesy applies to any time of the year, the courtesy of “thinking before you sharing weather-related posts” especially applies to the colder months of the year.

As a meteorologist, I look at a look of computer forecast model data daily. This is often referred to as “guidance” for a reason; these models are designed to “guide” the decisions of meteorologists while making a forecast. Sometimes the guidance is wrong, and sometimes it is right. Sometimes one model will propose one solution, and other model will have a different idea of how the weather will change.

You may have seen some of this guidance without even knowing it. If you see a map of snowfall totals that doesn’t look like a human being created it, that’s likely computer model guidance. It’s raw computer output, so it’s not a forecast. That one computer forecast model may look very different from the model run before it or different types of computer forecast models. But all you likely see in that social media post is what one model at one time thought. It may not be current; it may be a map saved from years ago and just re-posted.

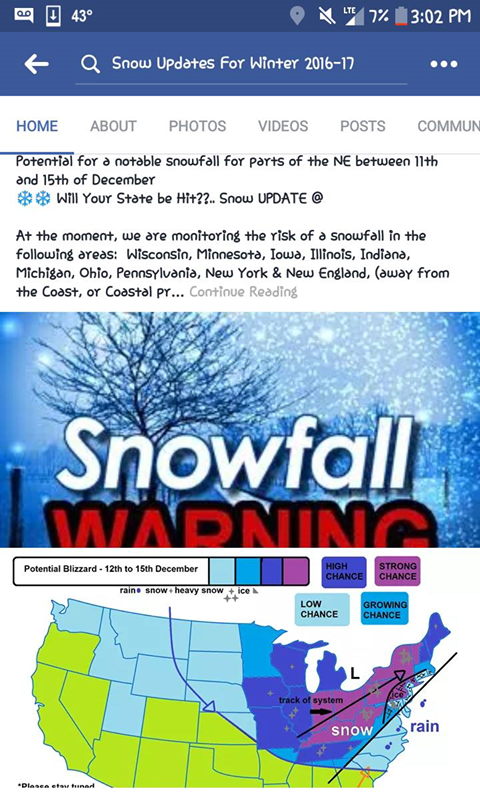

Sometimes the maps you see are created by a human, but not by a meteorologist or someone with years of forecasting experience. For example, someone messaged me this screenshot from the other day on Facebook asking if it was true:

Who was this created by? Do you know them? Did their forecast from last time verify? These are questions you should ask yourself. This post had hundreds of shares when I researched it. Why? Because it’s scary. Blizzards are rare. True blizzard conditions usually don’t cover multiple states and aren’t forecast 5 to 7 days in advance. A lot can change in a span of a few days, especially when the system hasn’t even developed yet. But it gets shared on social media because it’s potentially scary.

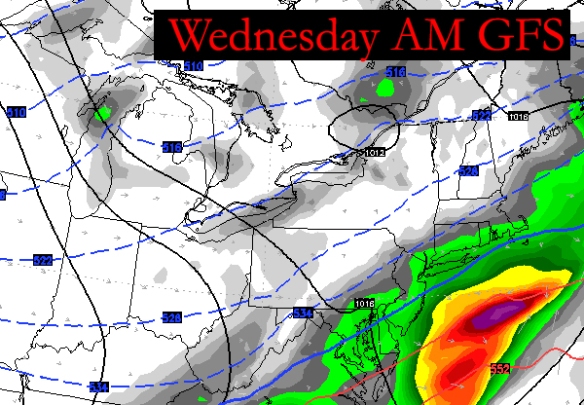

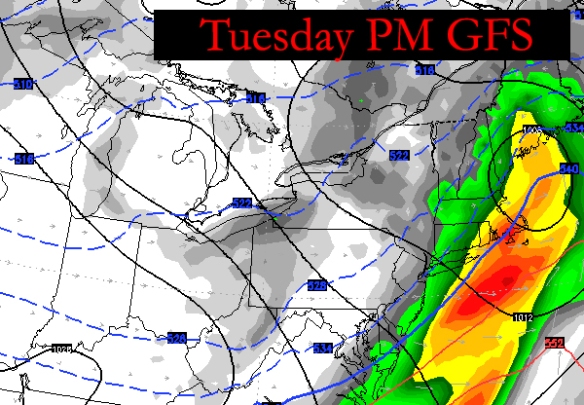

How often do forecasts change in the weather world? Here’s a forecast for atmospheric pressure (black lines) and precipitation (colored contours) from Wednesday morning’s GFS model for the Ohio Valley, New England, and Great Lakes for 7am Monday morning:

Cincinnati looks dry. Here’s what the same model (GFS) had forecast for the same time (7am Monday) 12 hours earlier:

Cincinnati also appears dry here, but notice a forecaster using this model in Boston may have some trouble because precipitation amounts differ.

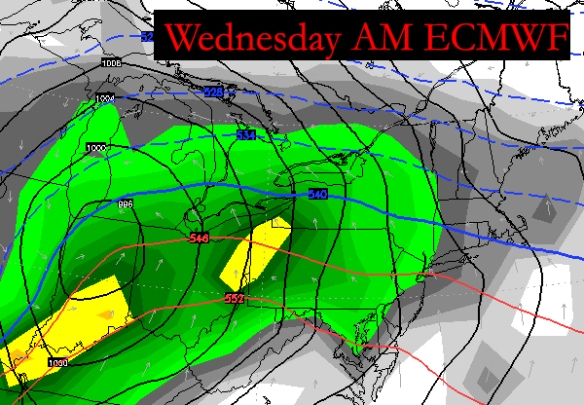

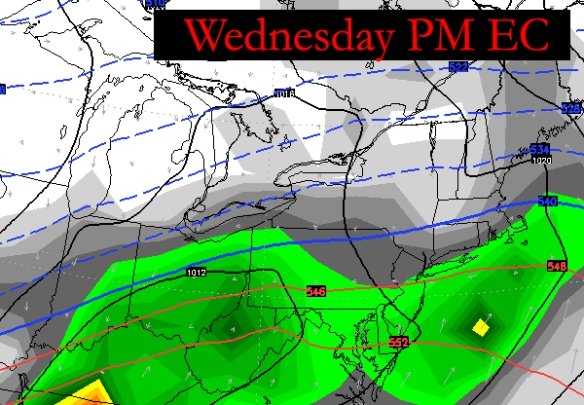

Let’s take another model, the ECMWF. Many meteorologists feel, over long periods of time, that it’s more accurate than the GFS. Is it? Here’s the forecast for atmospheric pressure (black lines) and precipitation (colored contours) from Wednesday morning’s ECMWF model for the Ohio Valley, New England, and Great Lakes for 7am Monday morning:

That’s a lot different that what Wednesday morning’s GFS model showed. That’s also a lot of precipitation. Some of it may be snow and some of it may be rain, depending on the temperature at various levels of the atmosphere. Here’s what the ECMWF had forecast for 7am Monday just 12 hours earlier:

That’s quite a difference in 12 hours. Precipitation amounts are much different in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes…plus the center of low pressure (closed off black lines) is in a much different spot.

So which one is right? That’s why meteorologists go to school for 4 years to study math and science. They throw the book at us and teach us how these models behave and work. What isn’t learned through education is learned through experience. This knowledge is not a part of a social media post showing massive amounts of snow, ice, cold, and a blizzard days or weeks out. Realistically, a social media poster wanting “likes” will post Wednesday morning’s ECMWF precipitation forecast because it’s scary and (if it verified) would be quite disruptive to travel.

So before you share a weather-related social media post, think of these:

- Who posted this information? Are they a meteorologist? Do you know them? Do they actually forecast the weather, do or they just post computer forecast model graphics? Have they been right before? Do you trust their forecasts?

- Who shared this information? If it’s a trusted source of information, then it’s probably giving you more truth than lies. If it’s a friend that shares everything and anything, then it’s probably a good idea not to share it and go to a trusted source.

- Did they post model output or did they make an actual forecast? Odds are higher that the outcome they are predicting will be right if it’s an actual forecast (meaning it doesn’t just look like a computer made it). Remember, snowfall forecasts usually have ranges not specific numbers for cities because wise forecasters and meteorologists acknowledge variability and uncertainty.

- A forecast for a massive storm or hazard several days or weeks out – especially if it is a very specific forecast – is usually wrong to dead wrong. When it doubt, don’t share it.

- Computer forecast models often overdevelop areas of low pressure in the long range (7+ days), so of course they are going to produce big storms as you go farther into the future.

- Some meteorologists hype. It’s just a fact. I hate it, and you hate it. Don’t fall for the hype. Remember if that meteorologist or forecast got it right last time. When I say “got it right,” I mean “was responsible,” “not scaring you then changing their thinking last minute,” and “at least in the ballpark with amounts and impacts.”

- When in doubt, don’t share it. There are a lot of teenagers out there who have no formal training in the weather posting scary images just to get your attention and likes. Would you trust a teenager with your car if he or she said they were a mechanic, or would you look for someone with experience and certification in their field? Education and experience aren’t everything, but it should count for more than something.