Data is really, really important to any business that matters. Data is being used to not just get a heartbeat on what customers are buying and using; it’s being used to drive decisions within the business. As I highlighted yesterday, companies are spending large amount of money (and their profits!) to better understand their customers’ behavior and purchasing profile.

Alternatively, meteorology requires quality data. Looking at surface, radar, satellite, and upper-level trends is a very valuable part of creating a forecast, but it will only take you so far…perhaps 12 hours into the future in some but not all situations. Computer guidance is needed to make forecasts that are longer-term. Knowing where severe storms will develop, where that hurricane will go, and how much snow will accumulate requires data and an understanding of it.

Meteorology isn’t a rewarding science unless the results are shared with many; there is little value in knowing where a storm will go and what impact it will have if only you know what the forecast is. If emergency managers, state officials, and the public know where the tornado is moving and what impacts a city will get from a tropical system, the information is far more valuable and can be used to make and inform other decisions.

Unfortunately, meteorologists can’t just download their analysis and knowledge into other people’s heads. The world would be a much smarter, better place (I hope) if we could freely exchange information and insight by installing it directly in a brain…but that isn’t the case. This requires a meteorologist to communicate their insights, conclusions, recommendations, and the data that supports all of these decisions. The conclusions, recommendations, and insights are valuable, but people and decision makers want to see the data for themselves to make sense of it.

The best meteorologists I know use quality data to tell a quality story. With so many options to get a forecast, it’s important to stand out; this unique story requires unique data. So why do so many meteorologists struggle with getting this unique data?

I want to emphasize the word “unique” here. Radar data is everywhere. Satellite data is everywhere. Model data is everywhere. Forecasts are everywhere. I’ve seen the National Hurricane Center’s track of the hurricane, and odds are good most have, too. Basically, if all or most of the weather communicators have access to or use the information, it’s not unique and people have no reason or incentive to choose one source over another.

So let’s go back to the question: why do meteorologists struggle with getting unique data? As someone that knows a fair amount about statistics, data, computers, and weather…programming is difficult. To be a successful programmer, you – among other things – must know:

- Where to get the data

- How to scrape or gather the data

- Format and quality control the data

- Know the tools to process and analyze the data

- Output the data or insights into a specific format

This process is not easy. There’s a lot weather data out there, and there are many meteorology-specific and non-meteorology-specific tools out there. These tools have a learning curve, and these tools take time to learn.

Secondly, finding the source of the data takes skill, time, and patience.

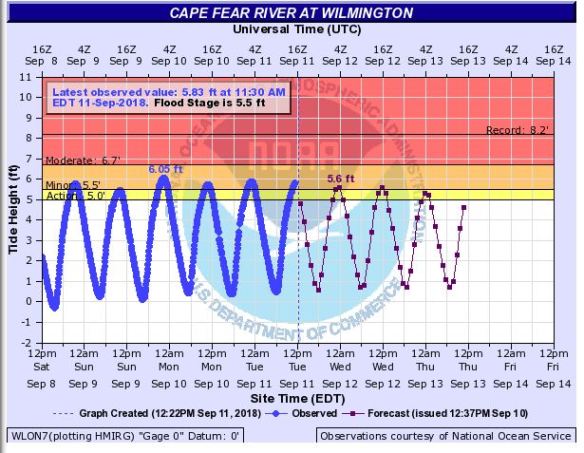

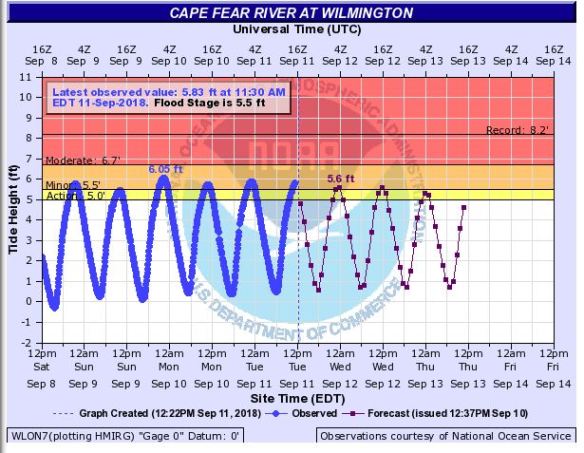

Let’s look at this problem. What does weather impact? How about rivers? Here’s a recent forecast for the Cape Fear River near Wilmington, South Carolina:

This is a helpful plot of information. It shows past, current, and forecast observations with tide information embedded. As I write this blog, Hurricane Florence is nearing the Carolinas, so flooding and river flooding information is even more valuable. So if I’m in the weather communication world, how do I share this information with my customers? I could screengrab it and share it out, but my bosses may not be happy with NOAA’s brand all over that data.

On the page where I pulled this data, there is an XML and RSS link to the underlying data in the plot above. Within the XML and RSS link, there are observed and forecast data points and corresponding times. We can download this raw data, process it, and export it to a weather communication computer system. So how do we get the data from where is it to where we want it? The answer is: figure it out! Don’t get defeated, don’t get overwhelmed, don’t get angry; instead, research:

- What programming languages read and process XML and RSS data

- How to use those languages to write code and transform the input data into desired output data

- The ways to automate the process.

Next, you have to take the output and use it as an input for your weather communication computer system. That’s where your knowledge of the latter gets used to finish the project and tell a unique weather story.

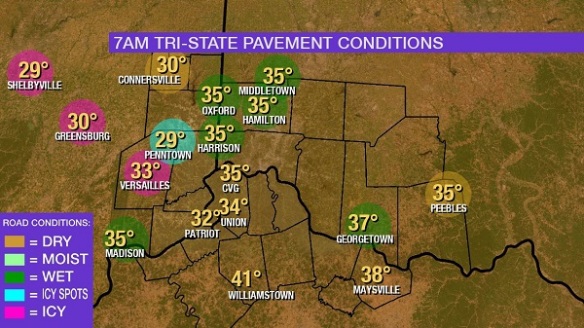

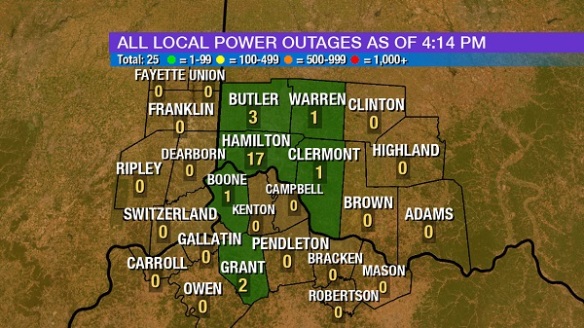

What else is impacted by weather? Power outages, air quality, river levels, road conditions, and more. Those who source the data (power companies, air quality agencies, etc.) typically publish their data in some form to the Internet. So how do you get that data from their final source to your final source? The answer is: figure it out! You can do this, but you have to have the passion, energy, and time to make it happen. It’s important to note that extra time to make a unique product today may save you a lot of time in the future.

Before you think that you can’t get information from that weather-related data website, you can. If you can get it in a browser, you can get the data. You just have to try harder to get it and transform it.

The ultimate goal here, as I alluded to in my blog post from yesterday, is to create a sustainable competitive advantage and cross-promote your product. If you own product A and B, you tell people on Product A to get a unique forecast on Product B, and you tell people on Product B to get a unique forecast on Product A, you’re likely to keep your company happy while also giving your company value.

Need an example of this in action? Try this:

This WTOL-TV’s real-time school delay and closing map. That’s data from an external source (a school closing/delay crawl system or the backend where schools districts report their delays) being inputted into a broadcast machine and colorized/formatted in the machine’s software. There is no doubt in my mind there is (automated) programming here to both export and import the data from one system to the next and to convert the output of one source to an input for another system. This is impressive work, and this is the only place I know that can show this type of data to customers! This took programming, weather communication system, and local school district knowledge plus time, effort, and – perhaps most importantly – passion.

This tweet from Ryan Hoke at WAVE-TV in Louisville, Kentucky shows rainfall data from Louisville Metropolitan Sewer District rain gauges. The data is freely available here. You could import the data straight into Microsoft Excel (which is NOT a programming tool!) and export it out, but there is likely programming going on in the background here to parse the table of rainfall totals. How did Ryan made this map? He saw the challenge, and he figured it out! It’s not incredibly easy to pull this data; some websites have easy access to data, and this site is not one of them. But you can do it!

These are two (rare) examples of importing unique weather-related data into a weather communications system. The company brand is intact, and the freely (well, seemingly) available data is natively flowing into a system where data is shared. This process took a lot of time, effort, passion, patience, and perseverance…but these data can now be promoted, cross-promoted among platforms, and used in real-time to inform the masses.

But wait; there’s more. You can archive this data and leverage of the power of statistics to model out river levels, air quality numbers, and power outages. I know it can be done because I’ve done it.

As I write this blog post, Hurricane Florence is moving west towards North and South Carolina, prompting people to fill up and move inland. Here’s an impactful tweet:

If you dig hard enough on the Internet, you can find the raw data for this map and bring it into a weather communications system. What a great weather story element!

You have to work hard if you want to tell a better story than everyone else. If customers see value in your product, they will come to you to get that value. But there’s a downside: if you look like everyone else, have the same data as everyone else, and tell the same story as everyone else…you’ll have the same market share as everyone else and be as valuable as everyone else.

The ability to program and use data to drive business decisions and profitability is becoming more important every day. If you can’t leverage weather data to your advantage, your potential as a meteorologist is severely capped.