I woke up this morning to find the weather chatter centering on rain to snow from Monday night and Tuesday. Depending on what computer forecast model you believe, there’s also the potential for snow later this week, this weekend, and the start of the following week. How much snow and when? What will the impacts be on all of these rounds of precipitation? What about that shot of very cold air coming later this week? Then, as a I reached for my first sip of coffee, I saw this:

Which came first: an audience of viewers and readers obsessed with minute-by-minute forecast changes a week in advance or the meteorologists and communicators who feed the unnecessary need for 7,000 granular forecast updates before a weather event?

— Dennis Mersereau (@wxdam) January 27, 2019

This tweet invites several questions about you, but mainly: how often do you – the customer – need forecast updates, on what, and why? This tweet also invites a lot of questions about me, meteorologists, and other forecasters, but mainly: after a review of the data, what do I need to share about the forecast while also being responsible, and what do my customers want?

As a meteorologist, I can confirm there is a lot of computer guidance out there. There are American models, European models, Canadian models, short-range models, long-range models, and even models that attempt to predict what the radar will look like in 15-minute increments. You could spend all day looking at guidance, but the benefit in reviewing all of this information is a forecast, or the best theory on what will actually happen.

The cold, hard reality is that customers don’t need to review all of this guidance. That is the job of a meteorologist. But not all meteorologists feel that way; some have become “model regurgitators.” They will give you a forecast, sure; they will also tell you what every single model run says along the way.

Let me give you an example of how this process plays out using one computer model runs over time. Here are recent 24-hour “snowfall” projections ending at 7am Friday from the GFS model:

Each snapshot here shows a “projection” (I put that in quotes because nearly all computer forecast models don’t directly forecast snow, so this is reality raw computer data with human logic that may or may not be correct layered on top of the data to get to a snow amount) from the GFS model. Each of these runs has different inputs of different quality. So which one of these models is right? If you watch the animation for long enough, you’ll see snowy runs and snow-less runs…and eventually you’ll realize that this model is not very consistent. This happens more often than you think.

Let’s go back to that potential for snow Monday night, and let’s see what type of precipitation the GFS “thinks” will be occurring (again, I’m using quotes here because the GFS doesn’t directly forecast what type of precipitation will occur at a given time. A human logic layer is applied here). Here’s the GFS computer projection for 10pm Monday night:

What type of precipitation will be occurring in Cincinnati at this time? Blue is snow, and green is rain. Well…this is complex. More recent runs are faster with line of precipitation and quicker to change over to snow, but we can’t ignore the fact that some recent GFS model runs suggest rain is more likely. We could broad-brush this and say “rain and snow to snow Monday night” (and there’s nothing wrong with that), but time matters when we’re talking snow. A rate multiplied by time will get you to a snow total. I just posted output from one model here, but the job of a meteorologist is to evaluate all model data, outcomes, and trends then make a forecast on what will happen. This means there is little to no value in posting model data for customers to review unless the meteorologist believes that model data is correct. This also means sharing what each model run “says” as it comes in is pointless.

So why is this happening? I have some theories:

- Some meteorologists and forecasters want attention, likes, and shares, and they will share model output to get that attention. The concept of “involving the customer in the process” or “bring them along for the ride” is merely a grab for attention. This can easily be countered by saying “I’m informing my customers,” but you can inform them with a forecast, not an attention-grabbing, knee-jerk, likely conflicting series of updates.

- It’s easy or at least becoming easier for meteorologists to share attention-getting weather headlines. Computer graphic machines can print out a snow amount for a city from a given model run to the tenth of an inch out to 5-7 days. Find a model run that generates extreme temperatures, severe weather, or big snow…and you’ve got a social media hit and a watercooler conversation.

- Meteorologists and forecasters (including non-meteorologists who have access to raw model data and maps) who gather significant attention for their extreme scenario posts often – over time – get an increasing market share, often drowning out those who are advertising more reasonable, modest, or less extreme scenarios. This often fuels misinformation about weather systems and the misconception that “meteorologists are always wrong.” Just because one forecaster cries wolf doesn’t mean they all do.

- Many forecasters lack the experience or education to evaluate model data and forecast the weather. Anyone can make a forecast or post maps, but making an accurate, detailed forecast requires skill. Unfortunately, extreme scenarios – or at least the risk of an extreme scenario occurring – will often win out over the voice of reason. In other words, the source of the forecast (or even raw computer output) doesn’t matter.

- Forecasts – partly as a function of inexperience in those who forecast or share computer guidance – are becoming increasingly wishy-washy. There’s a “chance” of extreme weather this week. Snow of 0-10″ is “possible” later this week. A temperature of -5° is scary, but a wind chill of -25° is even scarier. That wind chill could become -30° tonight…check back for updates! It is possible it could get worse! And that potential keeps many hanging on.

- The potential for significant weather often surfaces 5-10 days out. That means you’ll be strung along with “updates” for 5-10 days on one or more significant weather events. The scenarios could range from good to bad to worse, and you’ll likely see the scenarios change every 12 hours. There’s a lot of whiplash in the model world, so why are you being taken along for the ride? More importantly, why do you want to be along for the ride?

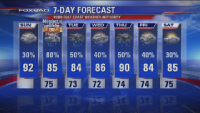

I’ve had a long standing concern in meteorology: the specifics of the forecast usually don’t matter. Here are some 7 day forecasts from Los Angeles TV stations:

So…a high of 76° and 78° today, and a high of 73° or 74° tomorrow. What’s the real difference here? Does it matter where you get your forecast from the next five days here? It doesn’t. It makes absolute sense that you get it the forecast from the easiest accessible place because there’s no significant difference between these forecasts. Additionally, there’s no need to check back for updates because if tomorrow’s high goes to 75°, who cares?

If there’s no risk for inconveniencing or hazardous weather in the next 24 hours, it doesn’t really matter where you get a forecast from. There are few weather scenarios (i.e. a blizzard, tornado outbreak) where you need to know what the forecast looks like beyond 24 hours. If you check your phone at noon to see what temperatures look like this afternoon and evening and you don’t see anything inconveniencing, that’s about all you need to do weather-wise for the rest of the day. If the forecast temperature for 8pm changes from 45° to 43°, was getting that update worth your time?

The best comparison I can make to this logic is like that of a sandwich shop. Let’s say you’re meeting a coworker for lunch 5 days from now. In reality, you just want a sandwich to be made when you get there. I believe it’s highly likely that you just want a sandwich to be there when you’re ready to eat 5 days from now; you’re not concerned with supply chain logistics, whether there will be a manager present at the store, whether the heater in the building will be working, and whether their shipment of meat and veggies will arrive at 4pm or 5pm on Thursday. I suspect you won’t be calling the sandwich shop every day until you meet your friend for lunch just to make sure everything is on track to get your sandwich. If the sandwich shop had a social media account, I don’t think you’d fine them posting about when their shipment of meat arrived at the dock, when their employees clocked in, and what temperature the thermostat is set at; even if they posted about this, you likely wouldn’t care.

Just like the sandwich, you just want a forecast. You go to a source of information that suggests what is going to happen. I suspect you aren’t going to a webpage and comparing what 5 different computer models say about the timing of precipitation and what the temperature will be for each hour in the next 5 days. I suspect you don’t care what the NAM model trend for the last 5 days has been, or what the median accumulation amount is from the latest SREF model. You just want the sandwich.

When you go to the doctor, you just want to hear his or her diagnosis. When you go to a mechanic, you just want to hear what the recommended repairs are and the associated costs. When your manager at work asks you to turn in a report, you don’t staple a separate sheet with your mathematical calculations to the report.

So why do it with weather? If it’s not a inconveniencing in the next 24 hours, go out and live your life. Forecast accuracy increases dramatically within 24 hours of active weather, so you might as well save your interest for that window and not go “along for the ride” on a computer model wild goose chase for days.