As I transition away from a chapter of my life centered on meteorology, I’ve realized I’ve learned a lot about what methods work in weather and which ones don’t. There are no hard-and-fast rules for success in meteorology or weather communication (and I’m continuously learning every day). After more than 10 years of weather, I wanted to share what I believe are 10 relatively easy ways to be a better meteorologist and communicator

1. Look to see what is going on. It is a huge mistake to just jump into the model world without reviewing recent weather trends. Where are the clouds, which way are they moving, and what altitude are they at? Where are the upper-level troughs and ridges? Where is their surface convergence and upper-level divergence of air? How fast and in what direction are showers and storms to the west moving? Computer forecast models frequently suck, so blindly depending on them will get your feet to the fire frequently. You should be spending at least several minutes each time you forecast looking at radar, satellite, water vapor, weather balloon, and surface report data before you even look at a computer model. While it is a mistake to expect models to match reality (they shouldn’t match), you can better gauge a given model’s strengths and weaknesses if you know what has occurred recently. As my father told me when I was a child, “You’ve got to know where you’re at to know where you’re going.”

2. Stop being everyone else. Just because there are many meteorologists in the country using 4-panel computer forecast guidance plots doesn’t mean you have to. Just because there are many meteorologists in the country that frequently say “those temperatures” and “these temperatures” does not mean you need to. Just because there are many meteorologists in the country that make heavy use of the terms “tracking,” “watching,” and “alerting” doesn’t mean you need to. Just because someone found success in forecasting an event or communicating the impacts of that event effectively doesn’t mean you’ll have the same success nor does it mean he or she will have the same success during the next event. There’s nothing that says you can’t dress for the job you want even if everyone else is wearing business casual. There’s nothing that says you can’t use forecast tools that the veteran in your office refuses to use. There’s nothing that says you have to put your forecast slides in a specific order. You don’t have to and you shouldn’t forecast and communicate like everyone else. You have to respect the spirit of the previous forecast (see below) and the ideology of where you work, but part of what you gets you a meteorology gig is your technique and individuality (at least I hope that’s how you’re measured). Your time is best spent maximizing your potential – whether it’s telling a weather story through explainer graphics, using long-range forecast analogs to give your customers insight beyond the week ahead, or developing unique data sets that can augment weather coverage – and not comparing yourself to other people. If everybody looks the same, success (pick your metric) is more likely to be evenly distributed.

Think of it this way: if you really like a store that’s 10 miles away, and a new company opens nearly the exact same store 5 miles away, odds are good you’ll start going to the closer store and – over time – both stores will have about the same number of customers (all other factors equal). A third and fourth store may open up, and the pattern repeats. Now suppose the store that’s 10 miles away has the special sauce, the secret weapon, and the sustainable competitive advantage that their competitors can’t reproduce; odds are good you’ll continue going to or start going back to that store. The moral of the story here is that the store 10 miles away from you dared to be unique and not like everyone else and got the customer base, attention, and income they earned and deserved.

3. Look at the previous forecast. If a previous forecast is available, you should be looking at it every time you forecast. The last forecaster – hopefully – spent hours looking over information before you showed up; they probably saw a few things in model guidance that you don’t see in the first few minutes of being in the forecast chair. Additionally, when every forecaster in the group reviews the previous forecast, there is more consistency, which benefits the customer and reduces the amount of work (in the form of updating) for forecasters. Refusing or simply not being interested in the current, persistence forecast signals arrogance and ego, and these elements of your personality will surface in time whether you try to hide them or not.

4. Make an actual forecast, and don’t be wishy-washy. Models suggest fog late tonight; odds are good many meteorologists will forecast “patchy fog” or “fog possible.” One computer model says showers are coming Thursday, but another says we’re dry. What’s the forecast? “Showers possible.” Showers are on the far outer-edge of an area of low pressure are approaching. In these scenarios, I often hear “there’s a slight chance for a few scattered showers.”

These are not strong forecasts. These are the meteorological equivalents of a punt in football. If you spend some time in the models or know your climatology, you’ll know where the fog will be favored and – with time and the right education – you’ll be able to forecast what the visibility will be at several spots. Fog is more than possible; it’s something every meteorologist should be able to forecast. When it comes to clouds and showers, you have more than just the latest model runs to look through; you can look the runs before them and the previous forecast. You can review the model trends for a given forecast hour. You can look at ensemble models. You can look at individual ensemble models members. You can look at satellite and radar trends.

Regardless of what you use, you should always make a forecast and run the risk of being wrong just like every other meteorologist in the world. You’re far more likely to gain credibility and respect from a customer if you give them the information they want to hear and be as specific as you can.

In a world where all the forecasts are “chances,” “possible,” “something to watch,” or some other form of hedging a bet, you want to be definitive, honest, and to the point. If you want to stand out from the crowd, don’t be wishy-washy.

5. Be conversational. It’s easier said than done, but communicating a forecast is just talking…so just talk. Talk in the same way you would to a friend sitting next to you on the couch about the weather; if you do this, you’ll avoid all of the terrible forecast crutch phrases. I’ve never had a meteorologist talk to me about the weather and say “those temperatures are going to fall through the 50s overnight;” instead, they say “we will fall through the 50s overnight.” You don’t talk to your mother about “windy conditions,” but you will say “it’s windy, but the wind will relax this evening.” Have you ever seen two people describe the weather for the “nighttime hours tonight?” I haven’t, but I’ve seen meteorologists do it. Have you ever looked up outside and thought the skies were beautiful? You said the sky was beautiful. I still don’t know what a thundershower is. If a cell produces lightning, it’s a thunderstorm; if it doesn’t, it’s a shower. Did you ever learn about thundershowers when you first learned about the weather in grade school? I didn’t because they don’t exist.

Important parts of communication are subject matter knowledge and relaxing. If you’re using crutch phrases, you’re either nervous or not as familiar with current weather and upcoming changes as you should be. Treat the camera as a neighbor. Treat your customer in the forecasts you draft as a friend you’re standing next to.

6. Review recordings of what you communicate, and work to improve what you didn’t like. When I was early in my broadcast career, I would record weathercasts from different television markets off of TV station websites. Of the ones I liked most, I would transcribe what the meteorologist said to text. I found several great weather phrases just by reviewing and typing out these recordings. I got in the habit of doing that in my next two jobs for at least a couple of months. I learned a lot, and I realized something important:

In my opinion, the best weather communicators spoke in complete, full sentences that flowed together and connected their content back to the forecast.

When you speak to another person either in person or in writing, you write in full sentences that flow together and often tie back to a central theme. That’s what communicating a forecast is all about: flow and emphasizing key points with inflection.

Whether you produce written, audible, or visual forecasts, record it and watch it. See what you did well and what you could have done better. Do this process for your presentations until you strengthen the good and eliminate the bad. Use pauses in your presentation. Inflect your voice when you’re highlighting what is important. If nothing else, avoid cliches and replace them with something better.

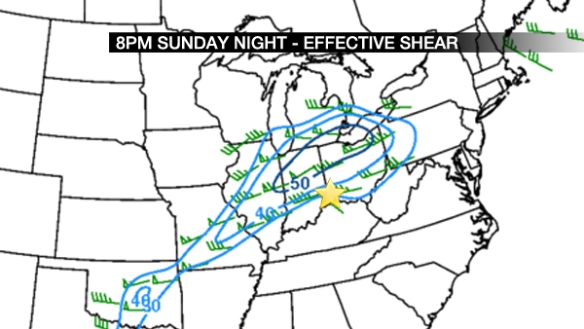

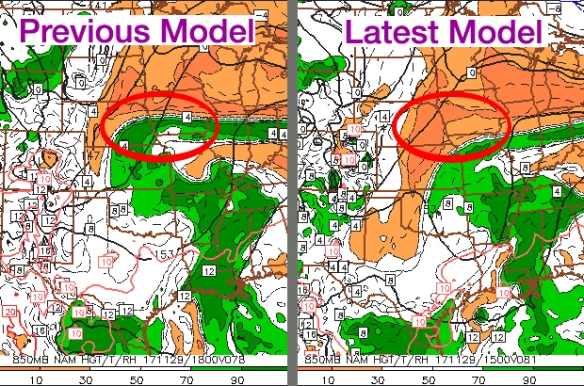

7. Don’t just be a “latest model” forecaster. When you forecast only using the “latest models,” you’re forecasting more of the noise and less of the signal. There will be anomalies, there will be large model shifts, and there will be situations – especially when a system comes ashore and is finally sampled by a weather balloon – when the forecast needs to be changed. Realistically, though, changing a low or high temperature by a degree gives your customer no additional value in most situations. What is the difference between 61° and 62°? Absolutely nothing. 31° versus 32° is a different story, however. Even with this acknowledged, though, remember the previous forecaster – assuming he or she reviewed the last forecast – carried over elements of the forecast before him or her.

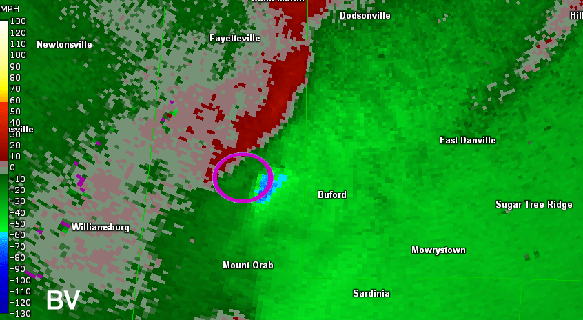

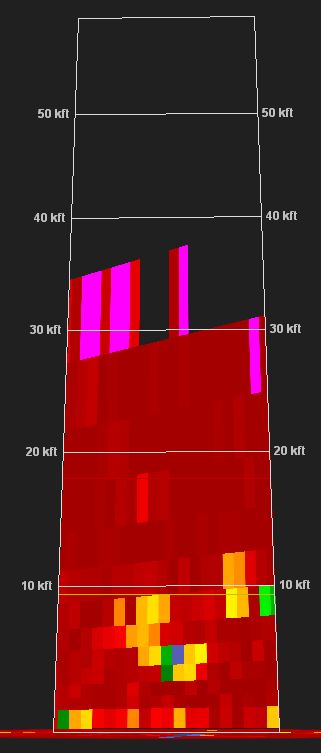

Being a “latest model” forecaster can prove costly. Here’s an example from this past Sunday using the NAM model. The latest model at the right shows a lack of clouds (tan, low relative humidity amounts) at 850mb or 5,000 feet above the ground. The model run before it had a significant amount of cloud cover (green, higher relative humidity amounts):

So which one is right? Of course, the real answer is a function of the previous forecast, what other models and their trends suggest, and what satellite and observed trends suggest (if anything at all). Blindly following the latest model here means you’ll likely remove and decrease clouds from the forecast. If this “latest run” isn’t a true trend, the next forecaster will just revert back to the cloudier solution; this will leave your customers are confused, show a lack of collaboration, and show your inability to make a reliable, accurate forecast.

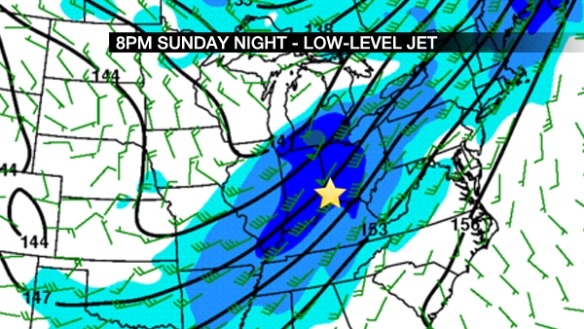

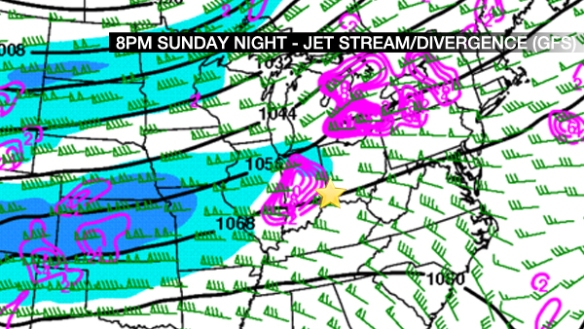

8. Don’t be a “mandatory pressure level” forecaster. Weather doesn’t just happen at 850, 700, and 500mb. When you’re first learning to forecast and getting introduced to models, you’ll see the classic 4-panel map like this.

There it is: 500mb (18,000 feet) vorticity, sea-level pressure, 700mb (10,000 feet) relatively humidity, and precipitation. In reality, this is not that helpful for forecasting. How about boosting this up to 6-panels?

The lower-middle panel showing 850mb relative humidity and the lower-right panel showing accumulated precipitation doesn’t really help us beyond what we had above. What if a shallow layer of clouds forms at an altitude of 3,000 feet developing in the afternoon? What if upper-level winds to the west carry a copious amount of high-level clouds to your forecast location? You’ll likely never see them if you are just focused on clouds at 700mb and 850mb.

You need to know temperature and dewpoint profiles in the atmosphere. You need to know the magnitude of shear and instability to see if thunderstorms will form. You need to look at more than just the temperature at 850mb and the surface to make a snow forecast.

If you’re only focused on the main pressure levels, you’re missing most of the atmosphere. Find ways and tools that can give you a more comprehensive view of the atmosphere.

9. Stop saying – or never start saying – “um,” “uh,” “like,” “you know” and other crutch words. These words may be “conversational,” but they make you look unintelligent, unprepared, and immature in presentations. I have seen people “um” and “uh” through life-threatening weather situations, and it’s not just painful to watch; it’s suggesting the speaker can’t handle the situation and don’t take people’s safety seriously. When you present weather information, you should be able to pivot. If you speak a sentence with words in an order you didn’t intend, can you still complete the sentence? If not, I encourage you to master and refine this skill. Can you explain the same weather in more than one way? Doing this will help you avoid the killer crutch phrases. Instead of saying “uh” or “um,” just don’t say anything. There is nothing wrong with 1 or 2 seconds of silence. If you’re reading weather bulletins, make sure you know where the key information is so you are not tripping over words.

10. Don’t idolize communicators. Being the best forecaster you can be means being the best version of yourself. If you’re good at using metaphors when explaining how weather works, refine and perfect that unique craft. If you’re good at connecting current or future weather to climatology, make that your thing. If you’re good at tailoring the forecast to people’s lives and events, do that. With any forecasting job you have, there will be rules to follow and guardrails for which you’ll want to stay inside. If you’re a National Weather Service forecaster, you’ll have to make aviation forecasts to fit certain specifications. If you’re in radio, you’ll have to use company taglines and only give forecasts for certain times of the day. If you’re in television, you’ll have to cover certain types of forecasts and make relevant graphics. While you should follow the rules, you should do everything you can inside of the guardrails to make a unique, interesting, and captivating presentation that showcases your best talents and skills. If you look like every other forecaster and forecast the same way, where is your value? Do everything you can to do what you love and highlight your value add. What got someone famous isn’t necessarily what will work for you. Focus on building what you already have.