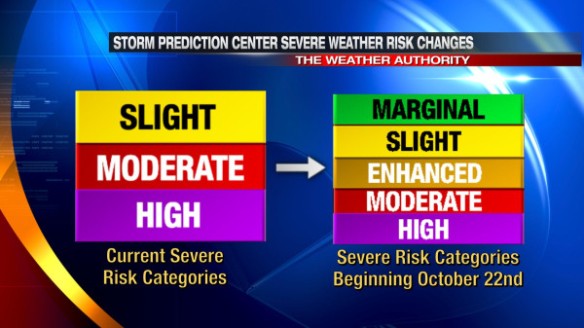

For years (really decades), the Storm Prediction Center has issued severe weather risks for the contiguous United States using “slight,” “moderate,” and “high” risk categories. Areas of the country that are most likely to see severe weather are typically placed under a “slight” risk for severe storms at least several times a year, a “moderate” risk up to a couple of times per year, and a “high” risk once every year or two when a major severe weather outbreak is expected.

But all of this is about to change. The 3-categories currently used to classify severe weather will soon expand to 5-categories.

In this interview, Greg Carbin with the Storm Prediction Center says “in the modern era, with the Internet, anybody can look at these [severe threat] graphics. So it’s our responsibility to convey that risk information in a way that’s a little easier to understand for the lay person as opposed to the expert. […] What we are hoping to do with these categories is convey that risk with meaningful words, colors, and numbers.”

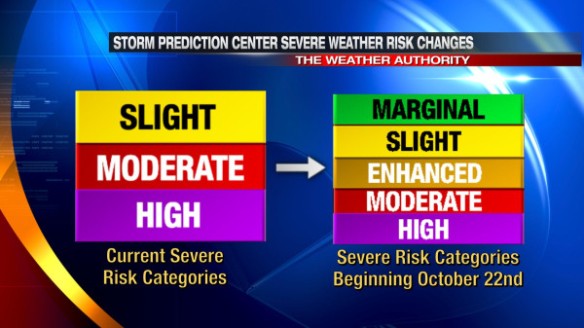

What does this change look like? Here’s a breakdown of what the severe weather risk categories are now and what they will be beginning October 22nd:

In simple terms, the “moderate” and “high” risk categories really won’t be changing this fall, and the current “slight” risk category will be broken down into 3 different categories (marginal, slight, and enhanced). Technically, the “marginal” risk will be a new category just under the current “slight” risk category.

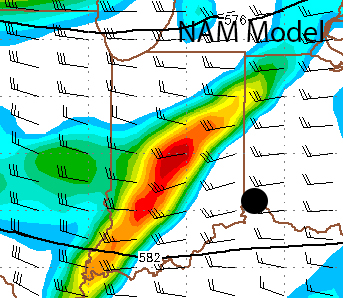

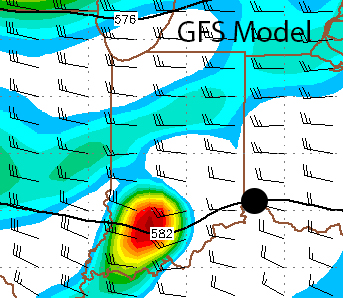

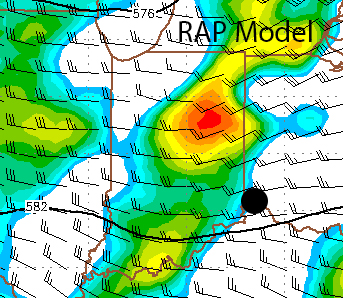

Higher-end risks will still be higher-end risks. Late in the morning of March 2nd, 2012, the Ohio Valley was covered with a “moderate” to “high” risk for severe weather:

Had this same severe weather outlook been issued using the 5-category severe weather outlook coming this fall, the risk for severe weather in the heart of Ohio Valley would have been the same:

The risk for severe weather would have been labeled differently for the northern Indiana, northern Ohio, and parts of the Tennessee Valley.

The changes from SPC were really made to break down lower-end severe weather threats more. Last Tuesday morning, a “slight” risk for severe storms was issued for much of New England:

Had this same outlook been issued using 5 severe weather categories, a “marginal” risk for severe storms would have surrounded the “slight” risk from central New England through the Carolinas:

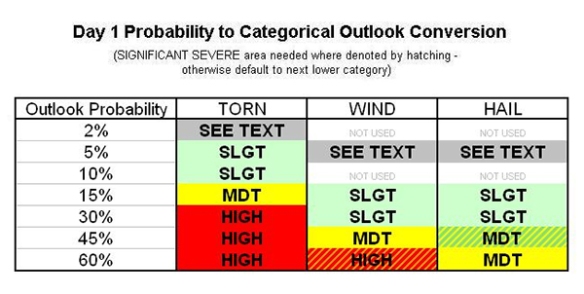

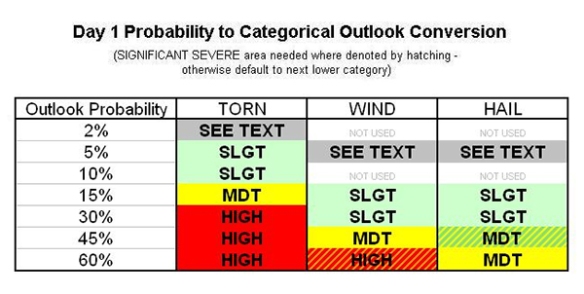

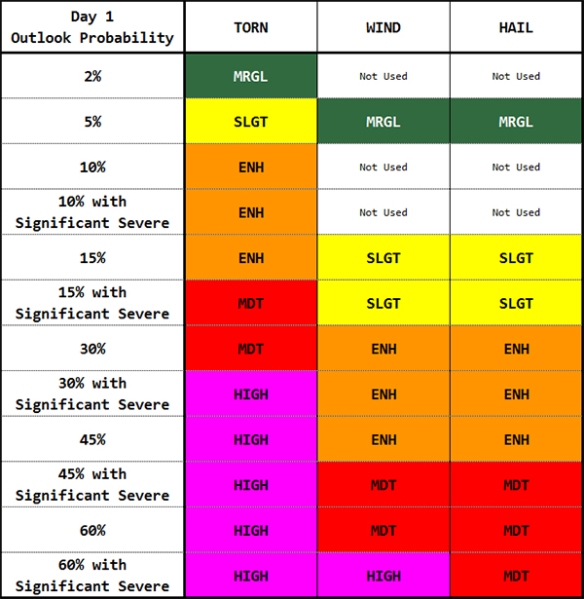

If you’re confused with all of the changes, you’re not alone. If you’re confused by the current outlook categories, I understand that, too. Here’s the probability table (based on a severe weather report occurring within 25 miles of a point) used by SPC forecasters to draw the severe weather threat for the current day:

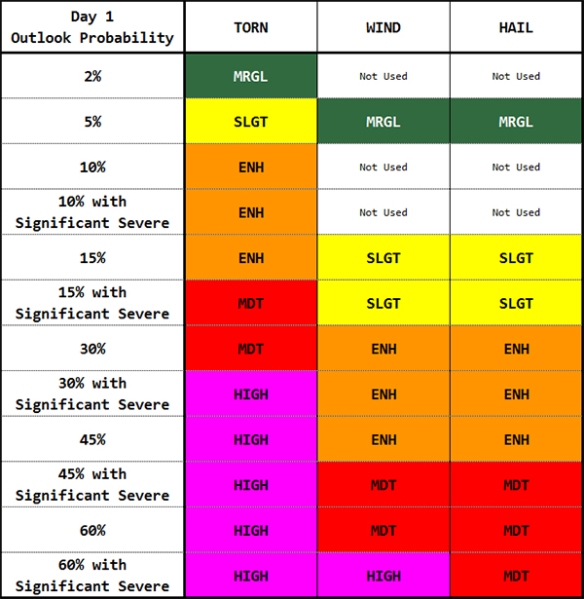

If you think that’s messy, here’s the probability table SPC forecasters will use to issue severe weather outlooks beginning October 22nd:

There are different tables for days 2 and 3 of the forecast. Making these forecasts is a challenge given model uncertainties and forecast time constraints. Creating these outlooks is not an easy job.

Why are the outlooks changing? I’m not entirely sure, and I don’t think the public does either.

I’m not so sure a change is needed here. More importantly, I’m not so sure the general public is familiar with and/or understands the current outlook categories and knows what the outlook categories mean. Changing what people don’t know by heart will likely come with a sense of confusion and questions about why there was a change.

Ultimately, this change should benefit the public, but I don’t think it will. Introducing new categories does not necessarily mean better understanding. As the tables above show, there is a lot that goes into placing a part of the country under a “slight,” “moderate,” or “high” risk. The public doesn’t understand the math behind each of these risks, but the subjective reasoning behind these risks isn’t common knowledge either. What does a “slight” risk really mean for my family? Honestly, meteorologists may disagree on what it takes for the Storm Prediction Center to issue a “slight” risk for severe weather in a given part of the country. If the lines are blurred or slightly blurred in the meteorological community, how will the public understand?

I don’t know of a meteorologist that knows the probability tables above like the back of his or her hand. I also don’t know of a meteorologist that had a complaint about the current SPC severe weather outlooks. There was no outcry to make a change from the meteorological community (at least not one that I knew of).

So why was there a change? The devil is in the details.

Over the years, there have been a lot of severe weather events that have occurred outside or barely inside of “slight” risk areas. A great example of this is the Evansville/Newburgh/Henderson F3 tornado of November 6, 2005. That area was in a 2% tornado risk area (not high enough alone to warrant a SPC “slight” risk) at 6:59pm on the evening of November 5, 2005. At 2am on November 6, 2005, the F3 tornado began near Henderson, Kentucky and continued through Evansville and Newburgh, Indiana. The tornado killed 25 and injured dozens. Outside of Tornado Warnings issued by NWS Paducah, there was really no suggestion from SPC that a deadly tornado would happen that night. This was a big “oops” moment from the Storm Prediction Center. If the severe hail and wind threat were non-existent, this 2% tornado area would have been in a “marginal” risk for severe storms given the new outlook categories coming this fall, and perhaps some would have paid attention to this tornado risk. Placing areas in a “marginal” severe risk may cause more to take the risk for severe weather seriously, but it may also lead to more “false alarms.” How many “marginal” SPC risks with no damage will it take before people ignore them and/or higher severe weather threats?

The names of the categories also bother me. A “marginal” risk downplays the severe weather risk when the potential is there – be it small – for something significant to happen. Also, how is an “enhanced” risk higher than a “slight” risk for severe storms? More importantly, what are the differences in the risk, and do the category names clearly suggest a difference in the severe weather threat? Did the SPC ask the opinion of social scientists to ensure their category naming convention would resonate with the public?

Discussing the severe weather risk categories with the people of Cincinnati on Fountain Square last week made me realize that people want information as simplified as possible when it comes to storms. Many I spoke with didn’t understand the need for SPC to change the categories. Many didn’t understand what “slight,” “moderate,” and “high” risks for severe weather really meant. Many don’t want to try and understand 5 different severe weather categories. Many just want to know how bad the weather is going to be on any given day or how it will impact their daily routine. These conversations reminded me that simple is better when it comes to discussing weather.

When I think of SPC expanding the severe weather threat categories to five, I think of the Homeland Security Advisory System, which was discontinued in 2011:

People never knew what the categories meant, and Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano said the scale provided “little practical information” when she phased out the scale in 2011. Let’s hope the SPC’s 5-category scale finds more success the DHS’ scale which was uninformative, nondescript, and unhelpful.