It’s November in the Tri-State, which means we are entering a secondary severe weather season. 11 tornadoes have been confirmed in the Tri-State during November since 1950. On average, 7 Severe Thunderstorm Warnings and 2 Tornado Warnings are issued in the Tri-State each November. The jet stream is getting stronger this time of the year, and the amount of instability in the air is getting lower as temperatures and dewpoints drop.

There’s a threat for severe storms late in the weekend, specifically Sunday night and early Monday, as a cold front sweeps into and through the Ohio Valley. While the Storm Prediction Center does not issue severe weather categories (marginal, slight, etc.) 4 or more days out, they have highlighted an elevated risk for severe storms in the Ohio Valley Sunday night:

Think of the yellow area as a “slight risk” of severe storms and the orange area as an “enhanced risk” of severe storms. Cincinnati is – more or less – in a slight risk for severe storms Sunday night and early Monday.

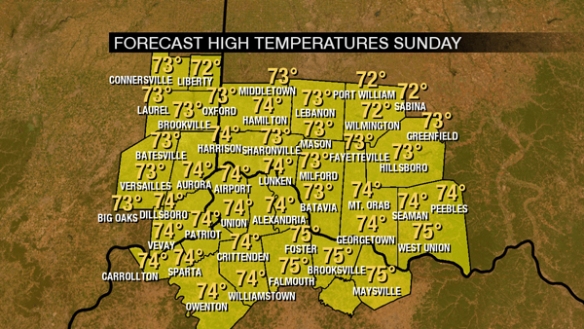

The environment that these storms develop and evolve in is important. It will be warm Sunday with high temperatures in the 70s:

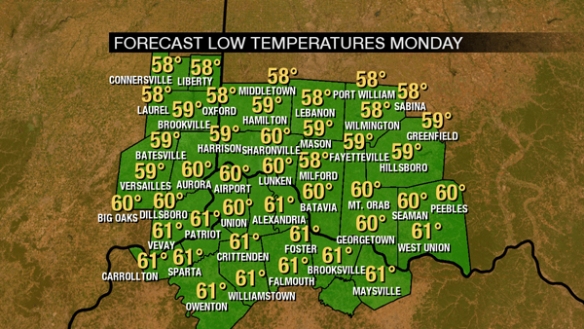

Low temperatures Monday will be around 60°, and it appears we’ll hit our low temperature at least a couple of hours after sunrise Monday:

Temperatures will likely fall through the 70s and 60s Sunday night. This is warm enough to support thunderstorms.

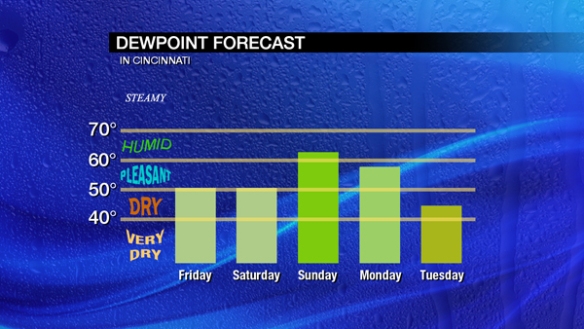

Moisture is another important ingredient for storms. Dewpoints will be in the 60s ahead of Sunday’s front:

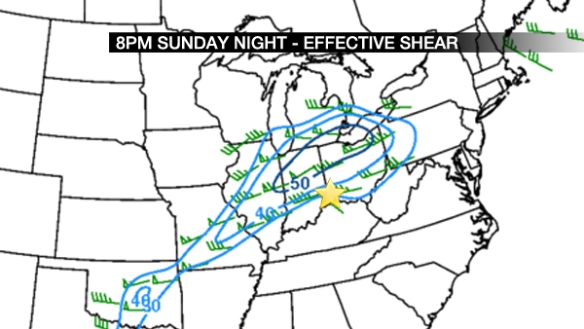

This is sufficient moisture for thunderstorms, including severe storms. Wind shear, the change in the direction and speed of the wind with increasing altitude, supports organized storms and the threat of severe storms. Here’s what the Thursday morning’s NAM model thinks for effective speed shear Sunday evening:

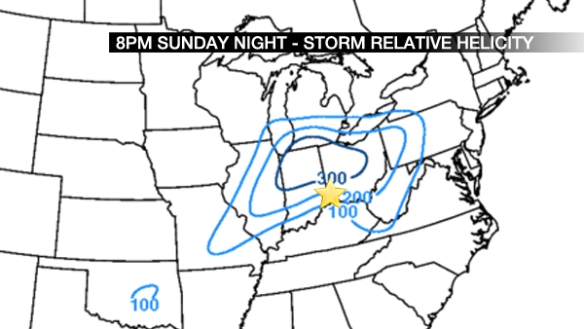

Numbers over 40 (knots) here support thunderstorms and severe storms. How likely are storms to rotate? Here’s what the same run of the NAM thinks for helicity (storm relative, indicating the likelihood for storms to rotate):

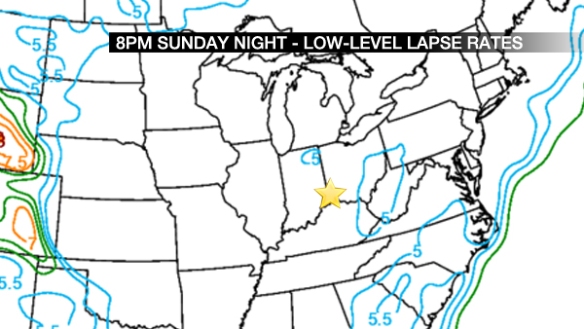

Number of 200 (m2/s2) here are significant, but we need other ingredients present. We need bubbles of air near the ground to rise rapidly if severe storms are to form; one way to do this is having a high low-level lapse rate, or a fast drop in the temperature going from the ground to a few thousand feet above the ground. Here’s what the NAM model thinks of that for Sunday night:

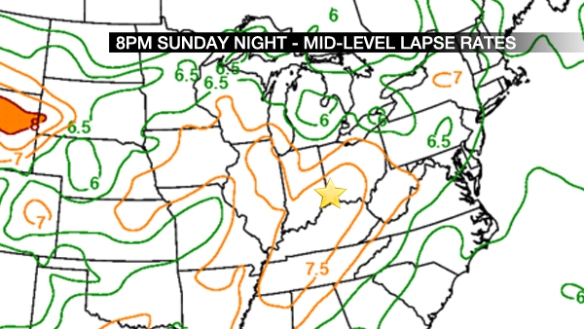

Those are low values, working against the thunderstorm and severe threat. How are the mid-level lapse rates looking?

These higher numbers are supportive of storms and severe storms if bubbles of air close to the ground are able to get higher up in the atmosphere.

How about instability and layers of stable air aloft? Here’s what the NAM model thinks:

The warm colors are instability, and the blue colors are stability. If severe storms are to form we want a lot of the former and less of the latter. Instability is modest, and stability is generous here. This works against the likelihood of storms and severe storms, but these ingredients are less important in the colder months of the year and more important in the warmer months of the year.

For lower-instability, higher-shear scenarios, I review what is called the SHERB parameter. As I discussed back in 2015:

While instability can often have a big influence on the chance for thunderstorms, it isn’t as important this time of the year. If thunderstorms are likely […], the SHERB parameter or index can be very helpful to a meteorologist in the colder months when looking a threat for severe weather. The SHERB parameter is helpful for getting a handle on a severe weather threat in the colder months because it focuses on temperature changes near the ground, lift in the atmosphere, and wind shear instead of instability (instability tends to be low in the winter even when we get severe weather).

Why is SHERB important? Unlike summer severe weather events which are driven by high instability and less of everything else, cold season events are driven by everything else and not often by instability. SHERB is a special blend of “everything else” that is important when gauging a severe weather threat…which makes it valuable when we don’t have summer-like heat and humidity. When SHERB values are high and the chance for rain and storms is high, severe weather is often a concern.

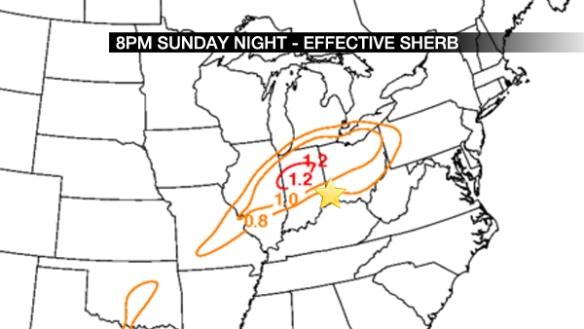

So what does the NAM model think of SHERB Sunday evening?

I’m looking for values of 1 or higher, which are focused northwest of Cincinnati. The 0.5- 1.0 values west of Cincinnati at this will likely drop slowly and translate east later Sunday night.

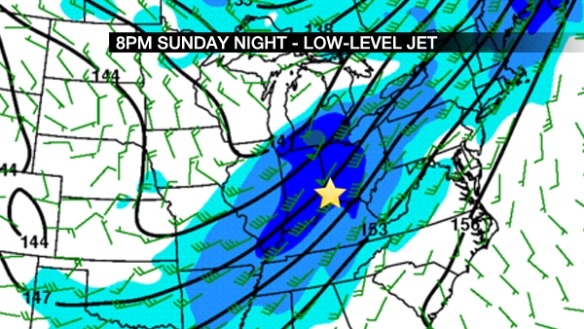

Wind speeds 5,000 feet or so above the ground are important, too; heavy rain can drag these winds aloft down to the ground. What does the NAM model think of these wind speeds?

These are significant, but not off the charts. If you’re of the math variety, these values are about 2-3 standard deviations above normal. This is enough wind to support storms and severe storms.

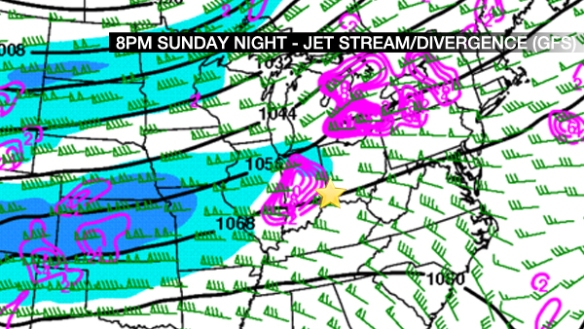

The positioning and strength of the jet stream is very important in the colder months of the year. Where does the NAM have the jet stream Sunday evening?

This is not ideal for thunderstorms and severe storms. The highest wind speeds are to the west (but still moving east) at 8pm Sunday night. Divergence (rising air) is in purple and positioned west and north if Cincinnati. What does Thursday’s morning’s GFS model say?

It has a lot more lift Sunday evening, and it has it stronger compared to the NAM model as it progresses east. There are clearly some strength and timing differences to resolve.

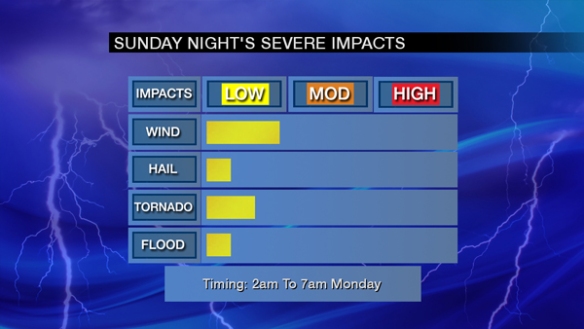

In summary, here’s what I’m thinking for Sunday night and early Monday:

This is still a wishy-washy threat at this point. We have good mid-level cooling, plenty of wind shear, and sufficient lift…but the lift timing and positioning are uncertain, instability and stability forecasts work against the storm threat, and we’ll need sunshine (even if filtered) to get the storm threat maximized.

There is plenty of time for conditions to change. Stay tuned!