It was the loudest thunderstorm I’ve ever heard in my life.

There was a cadence of thunder. Lightning resembled a strobe light. The lightning and thunder was so intense that you couldn’t sleep through it if you tried. It didn’t last a minute; it lasted 10 minutes. It wasn’t constant thunder and lightning; it was loud, bright, and constant. Based on the thunder and lightning alone, you knew something was wrong. And there was.

I woke up the next morning really not remembering what had happened hours ago. Sun was coming through the window, and the storms had moved out by 7am when I woke up. Sycamore Schools had been called off, and I remember hearing it on my alarm radio. Family members called asking if we were okay. There were tree branches down in my area, but there was nothing suspicious going on outside. I remember wondering who had moved our gas grill to the other side of the deck that morning; no human moved it.

It was clear once the TV was on that there was extensive damage on the other side of Blue Ash. It was likely a tornado based on the severity of the damage, but it was not confirmed at that point.

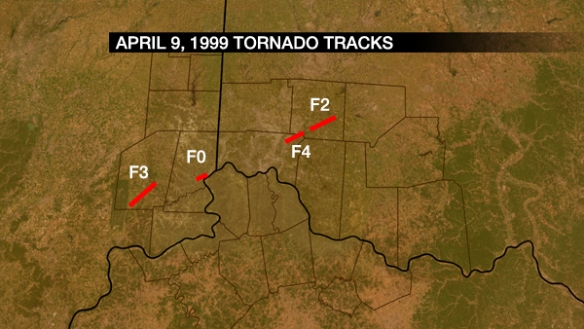

There 5 tornadoes in the Tri-State in the early morning hours of April 9, 1999. The map below shows 4 of them; an F1 tornado near Addyston is not shown:

A pair of thunderstorms were out to make trouble that night. One storm created two tornadoes in southeastern Indiana. Another caused damage in northeastern Hamilton County and southern Warren County. While the southern storm started strong, the northern storm would win out and cause the most damage that morning:

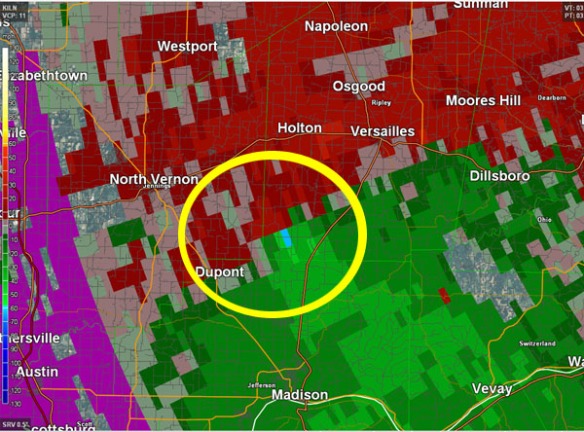

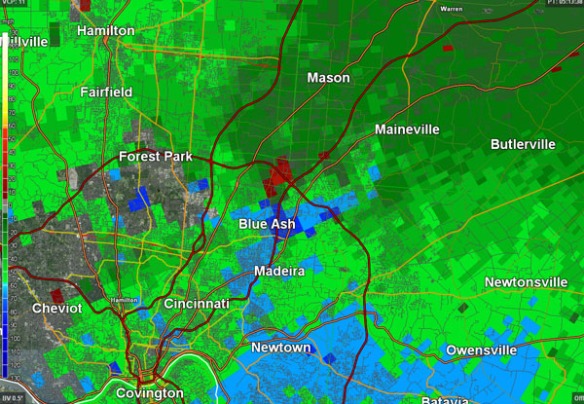

The first tornado of the night was an F3 in Ripley County, touching down near the Big Oaks Refuge and dissipating before it moved in Dearborn County. The storm relative velocity product showed strong inbound and outbound motion (in green/blue and red, respectively) in southern Ripley County just before 4am on April 9, 1999; the storm-relative velocity product is essentially the raw radar velocity product with the motion of the storm subtracted out.

While this tornado was significant and killed 3 people, a much larger, powerful tornado would develop less than one hour later from a separate thunderstorm.

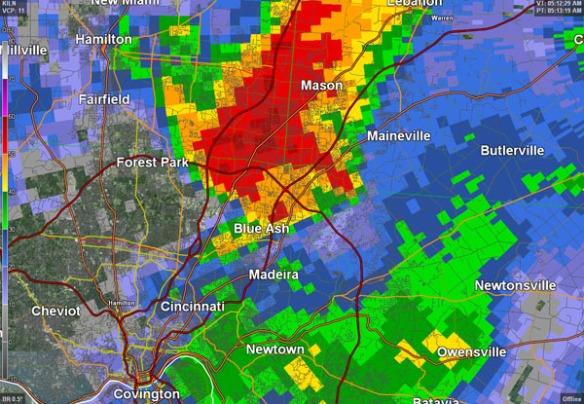

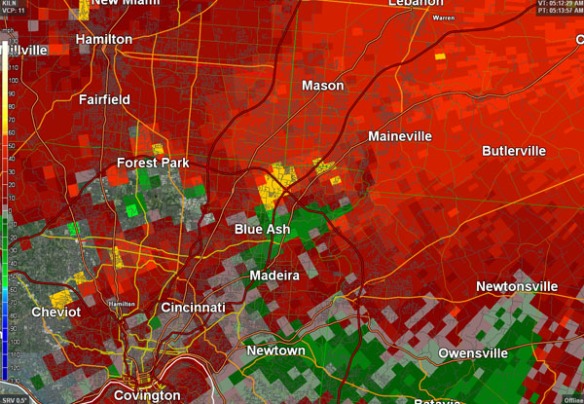

The 5:12am radar scan that night from the National Weather Service in Wilmington showed the classic “hook echo” forming just west of I-71:

The radar velocity scan showed intense rotation near Blue Ash at that same time. Blue colors in the image below show strong winds moving towards the radar, and red colors show winds moving away from the radar; the tornado is very close to where these colors meet:

The storm-relative velocity scan at 5:12am below shows the rotation as well:

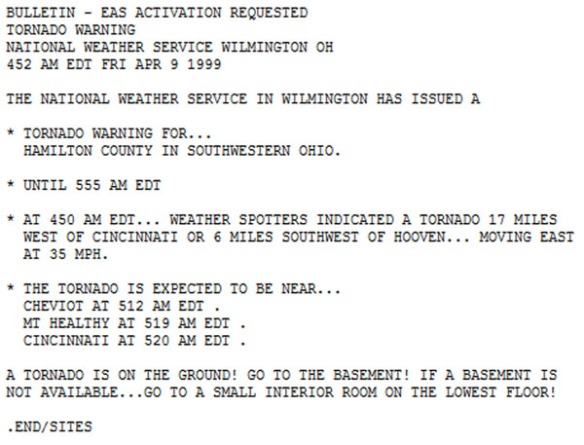

4 people were killed and 65 were injured as a result of the Blue Ash/Montgomery/Symmes Township tornado on April 9, 1999. More likely would have been killed or injured from this tornado had it not been for reports of a tornado and damage from trained weather spotters in Ripley and Dearborn County. This report was received by the National Weather Service at a critical, warning decision making time. The Tornado Warning issued for Hamilton County in the early morning hours of April 9, 1999 acknowledges a report of a tornado in southeastern Indiana minutes before Hamilton County was put under the warning.

These spotters saved lives that night.

There have only been 11 tornadoes in the Tri-State since 1950 to be classified as a violent tornado (given a rating of F4, F5, EF4, or EF5). The tornado that hit Blue Ash, Montgomery, and Symmes Township was one them. These communities had roughly 30 minutes of warning lead time to take cover, but this warning occurred on a night where the severe weather threat was not excessively high. Two Tornado Watch boxes were issued for the Tri-State that night, but there was no imminent threat of a tornado during the late local news. Most went to bed hours before the hours not expecting a tornado to crash into their house. The Internet was not used like it is today, and NOAA Weather Radios were not used as often. After seeing the damage firsthand, it is surprising that more weren’t killed or injured.

The event was also a game changer for how storms were covered by local TV stations. While tornado coverage was there, it revitalized the sense of urgency that storms bring. The loss of life that morning changed TV severe weather policies and how storms were tracked and covered.

With the tornadoes from April 9, 1999 included in the count, April is the most common month for tornadoes in the Tri-State (41 in total since 1950).

April 9, 1999 reminds us that tornadoes can and do strike how and when they want. They don’t wait until the sun comes up, and they don’t discriminate. Nighttime tornadoes are dangerous, and they are among the deadliest types of tornadoes because they cause damage when people are most vulnerable. Lessons were learned that morning 15 years ago; my hope is that we are better prepared for the next round of storms.