Weather has the power to be inconvenient and – unfortunately – can be a threat to life and property. The danger that weather presents depends on the situation; lightning may not be a significant threat to you in your home, but it is a very significant threat to you if you’re outside.

College football is starting up. Baseball games have been going strong all summer. Play has been delayed at GABP almost 22 hours this year alone this and over 27 hours as a team (home and away games combined). Rain, wind, hail, and lightning are all legitimate reasons to stop a game, but lightning seems to be the hardest reason for fans to accept. Here are two examples of people on Twitter not happy with a lightning delay:

Not only did they spell “lightning” wrong, but they don’t seem to understand the importance of lightning. Lightning can injure and kill, and exactly where and when lightning will develop is not easy to predict. The reasons why officials and stadium staff suspend games are not always easy to accept, but they are important reason.

This discussion about lightning during sporting events is just a small part of a larger discussion on weather safety. Weather safety is not just communicating risk; it is also about more than weather education and awareness.

We need to revisit the basics. When I say “we,” I mean everyone; it’s not just a thing for meteorologists. We need to do more than just revisit policies and procedures; we need to start simple. Here are some steps we all need to take:

1) KNOW SPECIFICALLY WHERE YOU ARE AT ALL TIMES DURING THREATENING OR INCONVENIENT WEATHER

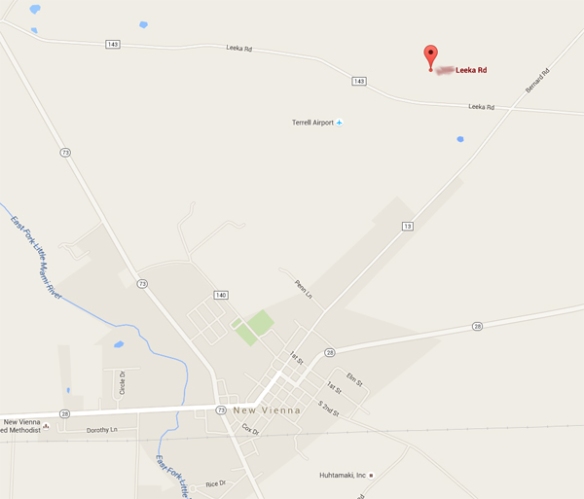

Some of you might laugh at this, but this is serious stuff. Too many people in this country don’t know where exactly where they live, exactly where they work, and exactly where they travel to throughout the day. It is very important that you know the county, the approximate distance and direction from nearby towns, and what time it is when there is a threat for inconvenient or storms. Do you know what part of the county for which you live? When you’re at the shopping mall, do you know what city you are near? When you’re watching TV at home and a meteorologist says a city where a storm is, do you know where you are relative to that city? You should. Geography and meteorology are interdisciplinary sciences. Knowing a storm is nothing if you don’t know where it is; on the other hand, if you know where you are but don’t know where storms are, you may be in trouble or unaware that significant weather is coming your way. Know local landmarks, and know where you are relative to those landmarks. Know what part of the city, county, and state you are in at all times, especially if there is a threat for thunderstorms or other threatening weather. Know where you are on a radar map.

2) WARNINGS RELATED TO THUNDERSTORMS ARE ISSUED FOR POLYGONS AND PARTS OF COUNTIES, NOT ENTIRE COUNTIES ANYMORE

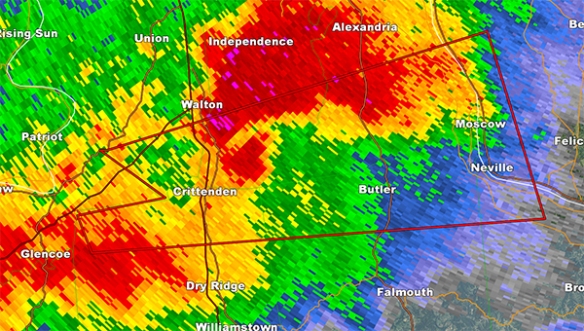

In 2007, the National Weather Service started issuing Severe Thunderstorm, Tornado, and Flash Flood Warnings as polygons (or shapes) to clearly identify where severe weather impacts are focused. These warnings are not issued for entire counties anymore; this was done in the past, but it is not done in the present nor will it be done in the future. It is possible that part of your county is in a Tornado Warning while other parts are not. Here is an example of a Tornado Warning from March 2, 2012 in northern Kentucky:

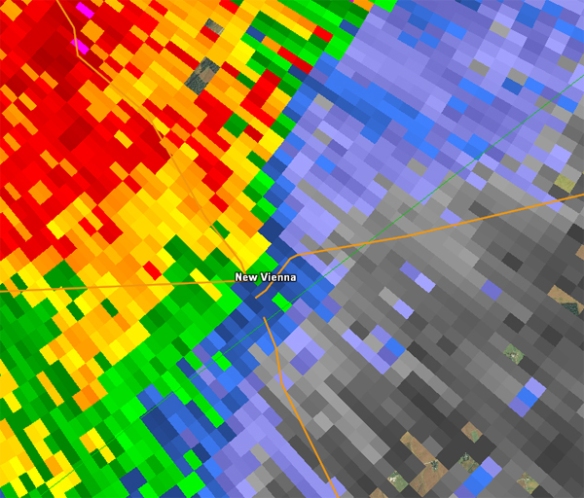

The Tornado Warning is outlined in red. The cities of Crittenden, Butler, Moscow, and Neville are in the Tornado Warning. Walton, Independence, Dry Ridge, Falmouth, Williamstown, and Alexandria are just outside of the warning. Here is the same Tornado Warning graphic with radar data included:

The radar shows intense radar echoes in the northern half of the Tornado Warning and also just north of the Tornado Warning.

The city of Crittenden and Dry Ridge (pictured) are both in Grant County, Kentucky. Suppose you live in Dry Ridge, and you hear a Tornado Warning is issued for part of Grant County. Should you take cover? Dry Ridge is not in the red box, and it is not in this Tornado Warning; therefore, you do not need to take cover at this time. However, there are strong storms in your areas, so you should be remain alert for warnings. This leads in easily into my next point.

3) NO WARNING DOES NOT NECESSARILY MEAN THAT STORMS WON’T BE INCONVENIENT OR THREATENING

Severe Thunderstorm Warnings in this country are issued when a storm is producing or is capable of producing wind in excess of 60mph, hail 1″ in diameter or larger, or a tornado. Severe Thunderstorm Warnings are not issued for lightning or heavy rain. Do not expect a warning to be issued if inconvenient weather is moving close to where you are. Heavy rain and lightning can still cause injury (or even death) if you put yourself in harm’s way. For your safety, you should always go inside when you see lightning. Heavy rain can lead to localized flooding; if you drive fast through heavy rain or standing water on roads, you can hurt yourself or get yourself in a bad situation, even if a warning was not warranted.

4) WARNINGS, WATCHES, AND ADVISORIES ARE NOT ISSUED FOR LIGHTNING

As I said above, a Severe Thunderstorm Warning has specific requirements for wind, hail, or a tornado. There are no lightning requirements for a Severe Thunderstorm Warning to be issued. If you’re outside in a non-severe thunderstorm, you can still be struck by lightning. It only takes one strike to injure or kill you. The odds of getting injured or killed go up rapidly if there is intense lightning in a storm or cluster of storms. Being safe means always going inside when there is lightning nearby.

5) YOU SHOULD HAVE MULTIPLE WAYS TO GET SEVERE WEATHER INFORMATION

Relying on one source to get severe weather alerts is a terrible idea. Watching television is a great source while you are awake, but your television will not alert you when you are sleeping. Having a NOAA weather radio in your home is important, as it can alert you with a loud noise day or night should a warning or watch be issued for your county and assuming you have your radio programmed correctly. Having a smart phone app to alert you to severe weather is great, but you should have more than one way to be notified of severe weather information. Cell phones can stop working, and batteries can die.

I would recommend having at least three ways to get severe weather bulletins. A correctly-programmed NOAA weather radio, a text alert service for your smart phone, television, and an e-mail alert service are all good sources to get this information. However…

6) A SEVERE WEATHER ALERT NOTIFICATION IS DESIGNED TO ENCOURAGE YOU TO SEEK ADDITIONAL SEVERE WEATHER INFORMATION

A text or e-mail alert service will typically tell you that your county or location has been placed in a severe weather warning. Due to character and text limitations, it is best to go to the television or your computer to verify where warnings, watches, and advisories have specifically been issued. Your text alert service may mention your county, but as discussed above, the National Weather Service issues severe weather warnings as polygons, not as a list of counties; this means that your location may not be in a warning, but another part of your county may be. It is important that you know and seek out this information; your life and property may depend on it.

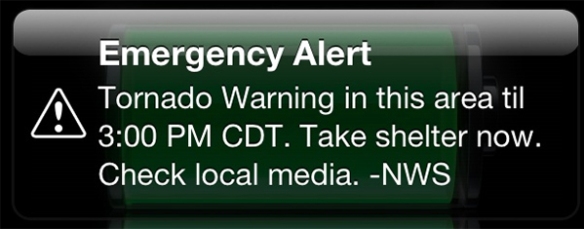

You may have seen an alert like the one above on your smartphone. These are called Wireless Emergency Alerts, a service created by FEMA, the FCC, the Department of Homeland Security, and the National Weather Service. While these alerts are great, they are incomplete due to text and technology limitations. “This area” is not specific. If you received this alert, you are encouraged to get additional severe weather information from another source and – as suggested – seek shelter immediately.

7) OUTDOOR WARNING SIRENS ARE MEANT FOR THOSE OUTDOORS

You should not wait until you hear an outdoor weather warning siren to seek shelter from a dangerous storm. These sirens are designed to notify those who are outdoors that threatening storms are approaching. Depending on location, these are usually issued for Tornado Warnings but may also be issued for Severe Thunderstorm Warnings. You should know when these sirens are sounded for your county. You should not consider outdoor warning sirens as the only way to get severe weather notifications, including if you are outside. As mentioned above, an outdoor weather warning siren should encourage you to seek shelter and additional information about where storms are, what threats they pose, and additional warning information.

8) TAKING ADEQUATE SHELTER IS ULTIMATELY YOUR RESPONSIBILITY

Severe weather alerts are great, but they mean nothing if you don’t take action. For example, this sign was displayed during the University of Cincinnati game this past Saturday night:

This was the student section on the opposite side of the stadium shortly after the photo above was taken:

This is not the right response. With all due respect to U.C. Bearcat fans, there should be no students in the stands with that message on the screen. While a Tornado or Severe Thunderstorm Warning was not in effect (and didn’t need to be), there was frequent lightning in the area. That was the reason for the message on the scoreboard. I feel a personal responsibility for the safety of these students given that I was one of the meteorologists that worked with the University of Cincinnati to evacuate the field and the stands.

If a meteorologist on TV says to take cover, do it. If the National Weather Services suggests going to the basement in their warning, do it. If you see lightning during your outdoor activity, take cover, and don’t wait for someone else to give you a warning. Whether there’s a warning or not, you should take your safety seriously. If you feel your life is in danger, take shelter and get out of harm’s way immediately. There’s no going back once you are injured or killed by a storm.