One of the tenets of meteorology is debate. Computer forecast models are consistently at odds with each other about the timing of intensity of weather systems. There are disagreements between meteorologists about the differences between what a mostly sunny, partly cloudy, and partly sunny day looks like. Some weather-related topics, like climate change, are politically charged and constantly challenged.

Of all of the debates I’ve heard, the one that surprises me the most involves when and how the National Weather Service should issue Tornado Warnings. A Tornado Warning is issued when spotters see a tornado, funnel cloud, or rotating wall cloud or when weather radar suggests (or in some cases, confirms) rotation in a thunderstorm is strong enough to produce a tornado. Based on the limitations of technology and the density of the spotter network, many Tornado Warnings do not verify. Radar is a tool designed to track rotation, but radar does not always match what a spotter in the field sees. Some spotter reports are unreliable or misleading, occasionally prompting warnings that did not need to be issued. Even with these considerations, however, the threat of a tornado should not be ignored for any reason. Whether weak or strong, all tornadoes are dangerous.

While there are certain situations and environments which will undoubtedly support and create tornadic thunderstorms, most tornadoes form in far less supportive environments. Most weak tornadoes last on the order of minutes, and larger, upper-level circulations in a tornadic thunderstorm usually don’t last much longer. Many of these weak tornadoes form from thunderstorms in a larger complex of storms. Meteorologists often call these MCSs or QLCSs (mesoscale convective systems or quasi-linear convective systems, respectively). Areas of rotation in a complex of thunderstorms can be hard to see due to the number of storms and given that most tornadoes in a QLCS are short-lived (on the order of minutes).

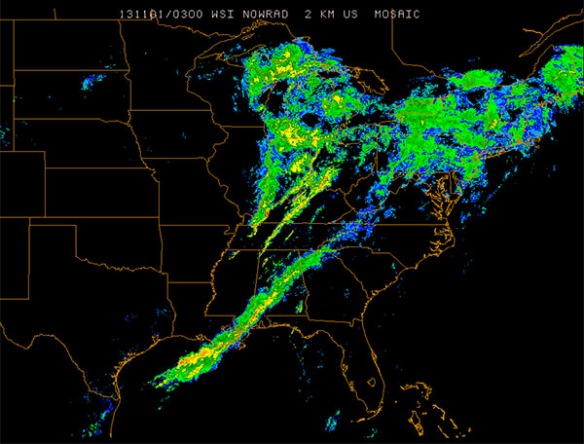

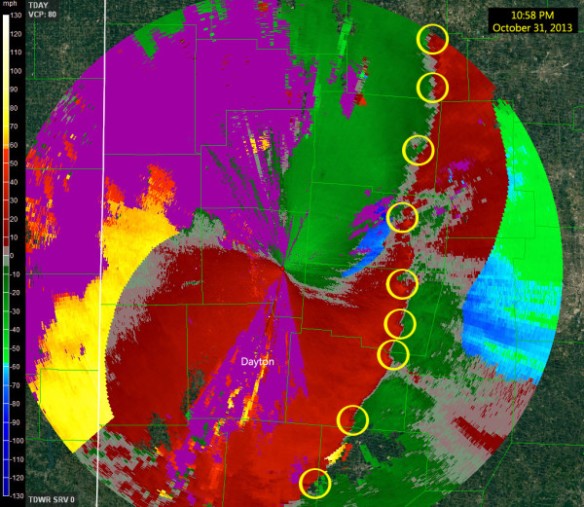

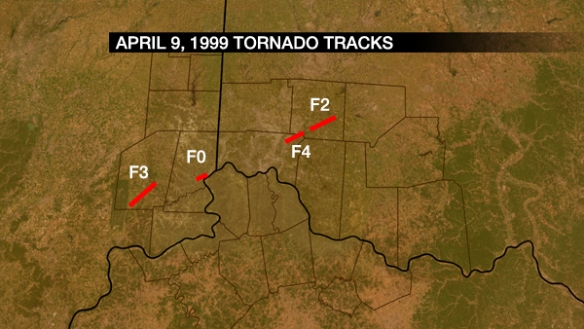

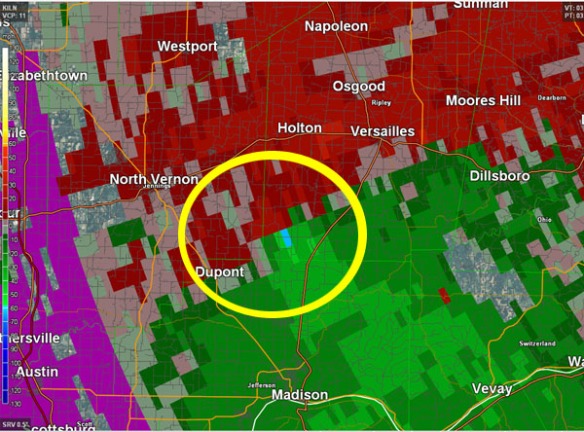

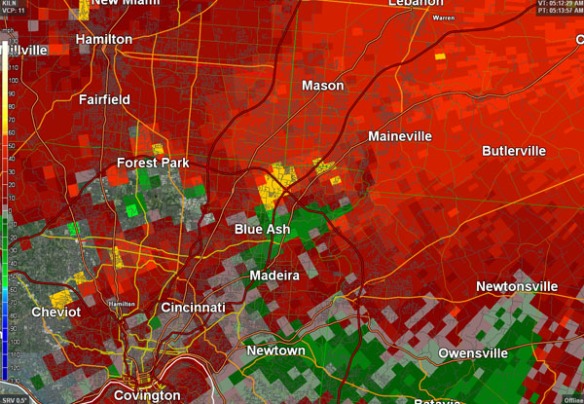

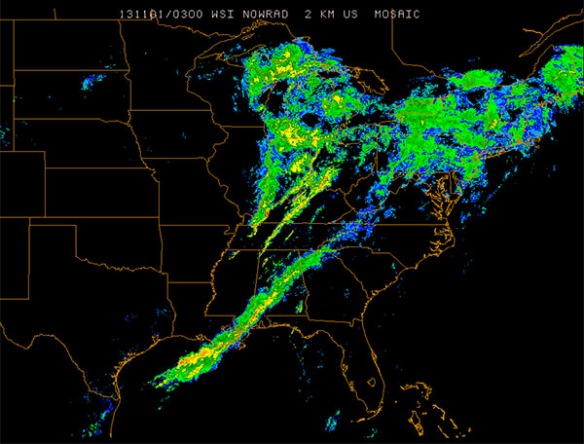

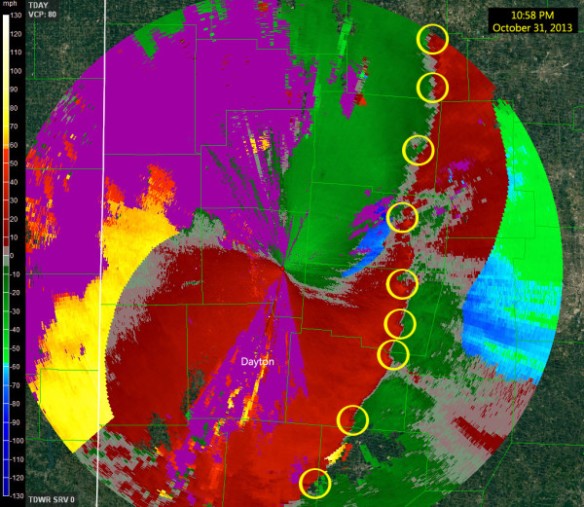

Consider the scenario we had on Halloween night of 2013. Here’s a radar snapshot late in the evening on October 31, 2013:

While it is very clear in this imagery that lines of showers and storms look strong and well-defined, using radar imagery some multiple radars is not very helpful for detecting rotation in thunderstorms. Using radial velocity data from a single radar site will be far more helpful for assessing how winds are moving relative to the radar. A snapshot of radial velocity data from the Terminal Doppler Weather Radar near the Dayton International Airport at 10:58pm on October 31, 2013 shows several areas where winds were moving towards and away from the radar in close proximity (circled):

There was adequate support for severe storms and tornadoes (especially weak ones) that night. While instability was not strong, the jet stream, upper-level flow, and upper-level support was. Knowing that that this entire area was in an area where severe storms are possible, which areas of rotation circled in the image require a Tornado Warning? Some couplets (zones of rotation) are stronger than others, but you’d have a lot of false alarms if you issued on every couplet.

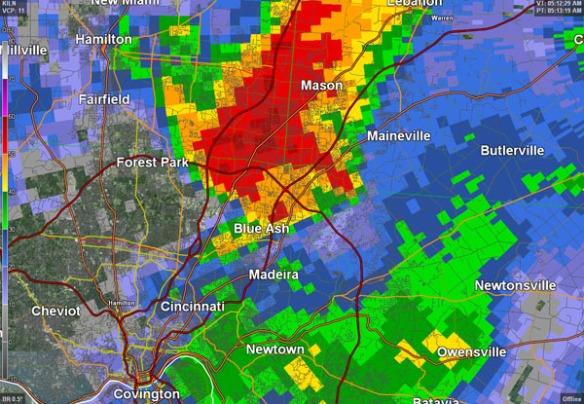

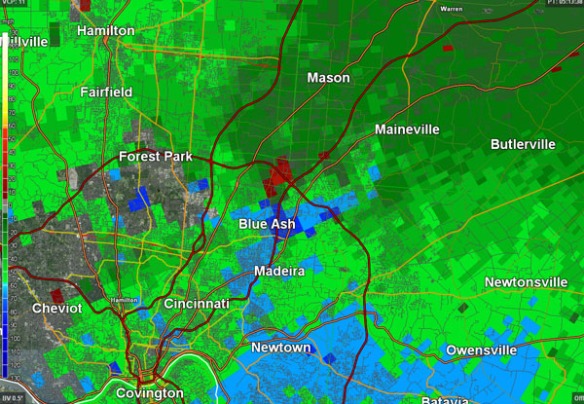

One tornado confirmed that night in the Ohio Valley occurred near Vandalia, Ohio. Even with a radial velocity scan produced by the radar every minute, the rotation the vicinity of the tornado is suddenly strong then suddenly weak in less than 5 minutes:

Even with high-resolution radar data, it is difficult to warn this community that a tornado is coming. It takes time for the National Weather Service to issue a Tornado Warning. It takes time for the media to break into programming to explain why a Tornado Warning was issued, show which communities are affected, and track the storm. It takes time for people to react and take cover. In this case, by the time all of this happened, the tornado had already dissipated.

While the tornado confirmed near Vandalia, Ohio on the evening of October 31, 2013 did not kill anyone, it injured 8 people. Unfortunately, many Ohio Valley tornadoes have killed people.

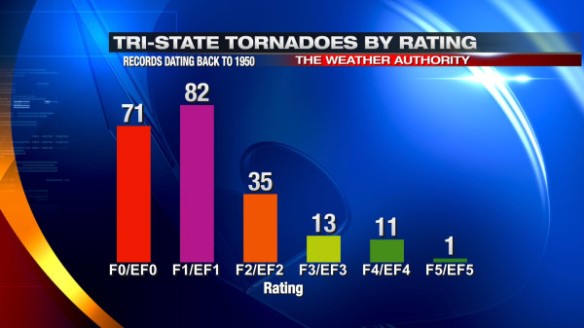

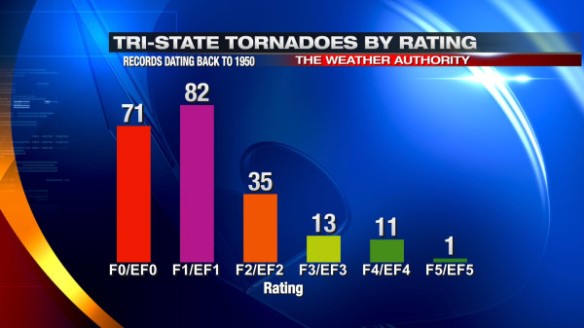

Historically, most tornadoes in the Tri-State since 1950 have been weak, receiving an F0, F1, EF0, or EF1 rating. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll classify “Tri-State tornadoes” as tornadoes since 1950 where any part of the tornado path is in the Tri-State. I’ll also count injuries, deaths, and damage caused by the entire tornado in my calculations even if part or most of these totals occurred outside of the Tri-State; odds are these “boosted” totals will be from stronger, longer-track tornadoes. Most tornadoes that have occurred in the Tri-State, however, began and ended in the Tri-State, so I will allow for this approximation.

The graph below shows that stronger tornadoes in the Tri-State have occurred less often than weaker tornadoes:

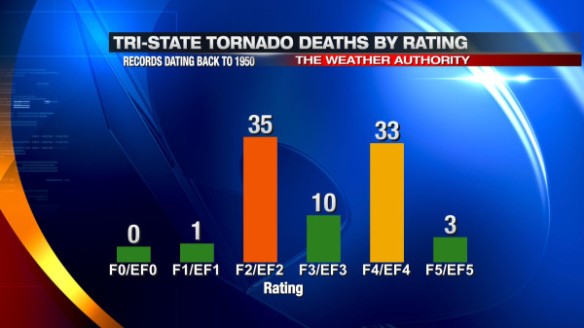

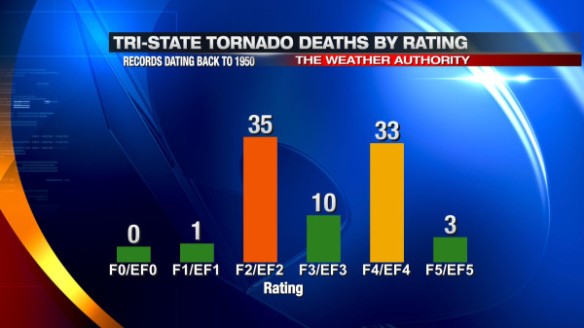

This is no great surprise; stronger tornadoes almost always require strong shear, instability, lift, and moisture. But do Tri-State tornadoes with a higher rating kill more people? Historical records suggest “yes,” but to a point:

It is important to note that weak tornadoes (tornadoes with an F0, F1, EF0, or EF1 rating) have only killed one person in the Tri-State since 1950, while strong tornadoes (with an F2+ or EF2+ rating) account for roughly 99% of all Tri-State tornado deaths.

I won’t go into great detail about it here, but I believe the spikes in F2/EF2 and F4/EF4 fatalities are more about what, when, and where the tornadoes hit and less about the strength of the tornado. The time of day, the time of year, population density in the path of the storm, and other factors likely contribute to the “spikes.” The F-scale and EF-scale are two different rating scales, and lumping and EF- and F-scale rated tornadoes into bins may also affect how the graph looks. The point I am highlighting is that stronger tornadoes tend to be killer tornadoes.

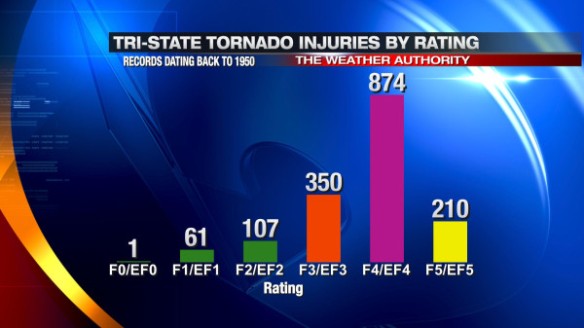

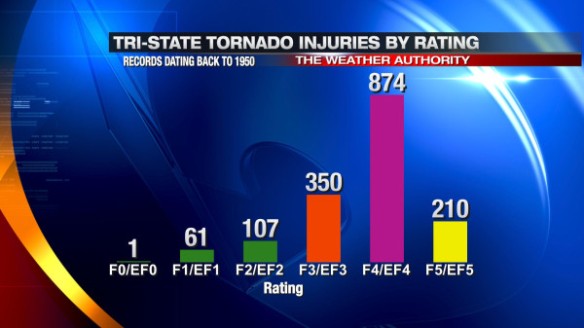

Injuries are more common than deaths with tornadoes, and – locally – more injuries have occurred with stronger tornadoes than with weaker ones:

There has only been one Tri-State tornado given an F5 or EF5 rating since 1950: the Boone County/Sayler Park tornado on April 3, 1974; this is likely the reason for a large drop in the injury count from F4/EF4 to F5/EF5 tornadoes.

So why issue Tornado Warnings for weaker tornadoes if they kill and injure fewer than F2/EF2+ rated tornadoes? If this were the case, fewer Tornado Warnings issued would lead to a lower false alarm rate, and fewer people would ignore Tornado Warnings. Why not just worry about the big tornadoes and ignore the small ones?

There are two big reasons. Here is the first:

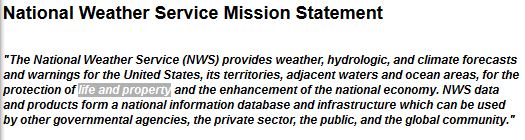

The Mission of the National Weather Service is to protect “life and property.” While protecting lives is of utmost importance, the Mission Statement also includes the words “and property.” The warnings that come from the National Weather Service and the tracking and alerting that broadcast meteorologists do is all in an effort to protect you and what you own. Regardless of whether they work for the NWS, in the media, academia, or the the private sector, meteorologists – as a whole – are committed to the NWS’ mission.

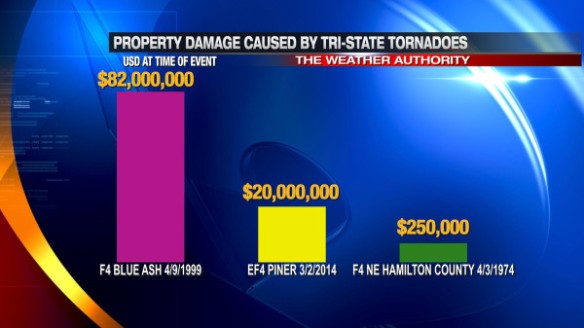

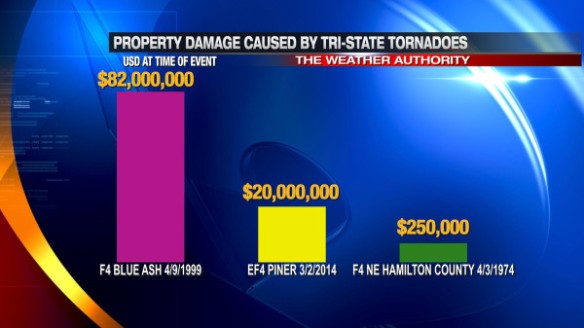

Some of the strongest tornadoes that have ever occurred in the Tri-State caused thousands if not millions of dollars in damage:

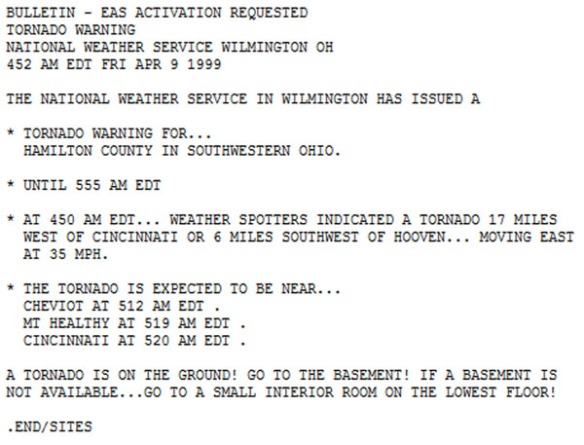

Even weak tornadoes can cause hundreds of thousands of dollars in damage. An F1 tornado in Dearborn County in the early morning hours of April 9, 1999 caused an estimated $250,000 (in USD at the time) worth of damage. Should we – the weather community – inform viewers when there’s an imminent threat of a tornado, regardless of whether it will injure people, kill people, or cause damage? Absolutely. People deserve the right to know what is coming for their them. Should the National Weather Service not issue a Flash Flood Warning if it will only cause homes to be damaged but not kill anyone? Should a broadcast meteorologist only cover a winter storm if it has the potential to be life threatening? Should meteorologist in the private sector only create a product or service that prevents injuries but doesn’t work to prevent deaths? The answer to all of these question is a resounding “NO.”

The second – and just as important – point is that discerning weak from strong tornadoes isn’t easily done in real-time. Despite incredible improvements in technology in the last 50 years, there will always be limitations to what a radar and spotter network can give a meteorologist. Radar doesn’t scan at the ground, and there will always be cases where a radar sees strong circulation but there is no tornado. Spotters are important for being the “ground truth” in the field, but spotters are not everywhere. Spotters can report a tornado and/or describe it, and radar can – in some cases – confirm a damaging tornado in progress. This, unfortunately, is where radar and spotters reach their maximum effectiveness.

Spotters and radar can’t rate a tornado. The EF-scale is based off of damage. In order for a tornado to get an EF rating, a National Weather Service survey team must survey the damage. Books and binders worth of documentation are often brought to the scene damage site so that the National Weather Service can compare what they see to a specific set of guidelines and give the tornado a rating. These surveys can take hours or even days.

As time goes on, we will learn more about how tornadoes form, how they dissipate, their environments, how to track them, and how to detect them with more accuracy. We will not, however, gain the ability to rate tornadoes on the EF scale in real-time. In other words, trying to rate a tornado as it cuts through a community is not worth our time. If we can’t definitively predict the rating of a tornado in real-time, why should we attempt to gauge which tornadoes will kill or injure people and which ones won’t? This is a dangerous game with no winners.

Tornado Warnings were created to warn those in the path that a tornado is imminent. Whether a tornado is radar indicated or confirmed by a spotter in the field, the threat for a tornado is real when a Tornado Warning is in effect. Some tornadoes will cause damage; others will kill and injure people. A meteorologist’s job is to warn, prepare, and educate. Daring to guess which storms will play nice and which ones won’t is best left to those who create the weather instead of forecasting it.